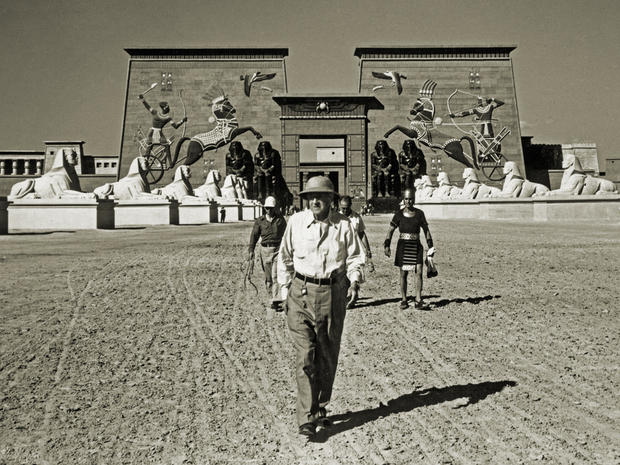

If any director followed the maxim, 'the bigger the better', it was Cecil B. DeMille. I will be frank: I enjoy his films, from the silent epic The King of Kings down to the splashy circus epic The Greatest Show on Earth to the opulent epic The Ten Commandments. DeMille, if nothing else, was consistent in his film-making.

I figure that my enjoyment of DeMille is not on course with many of my more intellectual counterparts, who are quick to dismiss him and his films as bombastic, overblown, hammy, grandiose, and even bigoted. To my mind, this is a case of throwing out the baby with the bathwater: mixing whatever hatred they have towards his politics into a hatred for his films.

I think DeMille is a wildly underrated director, both in terms of style and impact. Given that his primary interest was in entertaining audiences and giving the public what it wanted, he is trashed by the intelligentsia for not making films for them, exploring the deep and dark recesses of the human heart. I think DeMille could have done so if he was interested in doing so. However, I think DeMille had the goal of making films that would last, that would be watched again and again, and he has succeeded.

Think on this: few directors serve as verbs. There's Capraesque, Felliniesque, Spielbergian and Hitchcockian. Add to that one more: a DeMille picture is quickly understood as being above all, a BIG picture, an event. Now, while that epic quality of his pictures, especially in the latter period, has damaged his reputation among elites, the public at large, both during his lifetime and after, still love his movies because they are entertaining.

One thing people forget about Cecil B. DeMille is that he was one of the few directors to have a long career after the transition from silent to sound pictures. Sunset Boulevard had it absolute right: there were three great directors working in silent pictures: D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, and 'Erich Von Stroheim' (he could say Max Mayerling, but we all know whom he was actually referring to). Which one of them was the only one still standing?

It wasn't that DeMille was better than Griffith or Von Stroheim or more talented than them. I'd argue each was a genius in his own way, but it was because DeMille adapted the best of all three of them in two ways. The first was to work with the studio bosses to retain as much artistic control as possible while still understanding that, for all his trappings of director-as-tyrant, he was still an employee.

This point is what killed Von Stroheim. The second was to adapt to the advancing technology and make films the public would want to see. This is what killed Griffith, who was too attached to making old-fashioned films and was never quite able to move on to sound.

DeMille may be unpopular because again and again, he kept going back to the past and especially The Bible for inspiration. His big hit, The King of Kings, took direct quotations from the Gospels to make his biopic of Christ complete with color sequences, which show DeMille had some idea of where the future was heading. He had a great hit not just because the life of Jesus is known by the majority of Americans, but because he took Preston Sturges' advice before Sullivan's Travels: DeMille made a religious film "with a little sex in it".

I doubt Mary Magdalene was Judas Iscariot's lover, but by adding just a hint of decadence, DeMille manipulated audiences by introducing a sense of sin which Christ, in this case cinematically, could absolve. He did it again with the original The Ten Commandments and its remake when the Children of Israel give themselves to wild abandon at the foot of Mount Sinai. He did it once again with Samson and Delilah: that tale of the wanton woman seducing one of the judges of Israel. As any good director knows, DeMille knew how to grab the audience's attention.

Going back to The King of Kings, for all the trashing DeMille gets about not being able to direct actors, I would hold the scene where Christ (H.B. Werner) has a group of children before him. A little girl asks him if he can heal, and He says yes. The little girl promptly holds up her doll and asks Christ to heal her broken arm. Jesus looks a bit embarrassed by this request, but cleverly grants her request in what I think is an especially tender and touching moment.

Yes, there was a religious aspect to DeMille's pictures, and he may have been a devout Christian, rumors of mistresses notwithstanding. I stand by my view that DeMille understood that for a predominantly Christian nation or at least one that is Christian by default, these subjects would get them into theaters. I can't say one way or another, but I think DeMille had very few financial failures, so that's something to be said for his ability to understand an audience.

It wasn't all togas and crosses for DeMille. He could make contemporary films (although one of them, The Godless Girl, seems to mix the sign of the cross with the sign of the times, and the original The Ten Commandments has a 1920's setting mixed with the Exodus story). The one that has been vilified more than any is The Greatest Show on Earth. Few films are hated for winning Best Picture, but almost all of them have at least one defender.

When it comes to The Greatest Show on Earth, I ain't one. I don't think it was the Best Picture nominated in 1952: I think it was The Quiet Man, followed by High Noon, followed by Moulin Rouge, THEN The Greatest Show on Earth, with Ivanhoe bringing up the rear.

I will, however, stand up for The Greatest Show on Earth being great entertainment. Having seen it twice, I think it captures the best of DeMille: telling a small story (the love triangle between the circus manager, the trapeze artist, and her male rival) in a large canvas with both secondary stories (Buttons the clown who never takes his make-up off and the tortured romance between the elephant trainer and his Muse) with lavish production numbers, culminating in an incredible train crash which in 1952 would have been spectacular and even now is still pretty good. In a more formal review for The Greatest Show on Earth, I will speculate as to the myriad of reasons it won Best Picture, but I can't call it a lousy film because I was entertained by it.

Here, and in his final film as a director, the remake of The Ten Commandments, we can see what made Cecil B. DeMille one of the greats in cinema. He knew how to command and control audience emotion: how to excite them, how to entertain them, and how to hold their attention in spite of a very long picture. He understood how to keep a moving picture moving: going from one scene to another by always having something going on.

There is not much stillness in a DeMille film, and in a curious sort of way, modern directors could learn from him. I am aware that most critics masturbate to No Country For Old Men, but without going into too much detail I felt many scenes were endless and dragged on. It might do the Coen Brothers well to watch a DeMille picture to learn how to keep things moving.

As a side note, it's not my fault that The Greatest Show on Earth won. It's not even Cecil B. DeMille's fault that it won. Therefore both the film and its director should not be condemned for winning.

Now, I'd like to address this issue of DeMille being a bigot in his films. This may be a case of people attaching his political conservatism to his films. Yes, DeMille wanted members of the Directors Guild to take loyalty oaths during the McCarthy era, something I think was a terrible mistake. However, in his films there isn't much if any evidence for the charges of bigotry. The Crusades is not a diatribe against Islam but from what I understand remarkably respectful of it, especially for its time. In the remake of The Ten Commandments, he hints that the Princess of Ethiopia and Moses may have romantic interests in each other: pretty daring stuff for 1956. We also should remember that, despite DeMille's support for loyalty oaths, it was DeMille that broke the graylist against Edward G. Robinson and composer Leonard Bernstein by hiring them when no one else would.

In short, Cecil B. DeMille was a far more complex person than his persona hints at, and that applies to his films. I've always felt that the 1923 The Ten Commandments spoke to an era where people were becoming highly aware that their values in the Ten Commandments were slowly becoming subverted by the Jazz Age of speakeasies, gangsters, fast cars and faster women, and the need for speed & greed. The idea of a 'godless tyranny' oppressing the Chosen People and having to fight for their freedom with God on their side might be the story on the screen, but in 1952 with the Cold War in full strength, could it be DeMille was making an allegory of current-day politics wrapped within a Biblical epic? Perhaps DeMille was smarter than the elitist critics give him credit for...

Cecil B. DeMille's influence is still being felt. Steven Spielberg is probably the most DeMille-like director today. He, like DeMille, has a dynamic and almost flawless ability to give people films that above all entertain. Both are craftsmen in film-making, and it's no surprise. Spielberg has been open how The Greatest Show on Earth was a primary influence in his decision to go into directing: a case of one genius influencing another.

Both, curiously, have been criticized for being too popular, for making films that aren't considered deep. I would argue those criticisms of DeMille and Spielberg are wildly off the mark. Each, in their way, is a deeper and stronger director than they've been given credit for.

I find myself in an odd position. I'm one of the few people who is an open Champion of Cecil B. DeMille as a director and filmmaker. I think by and large he made great films, and that a lot of the bashing against him isn't based on the films themselves but on what people think of him personally. I don't care about a performer's politics, though I am always concerned that his/her politics will overshadow their work and advise to keep their political activities to a minimum. I judge the film itself, and when it comes to Cecil B. DeMille, I have yet to be bored by any of them.

I end with this: Cecil B. DeMille is a genius, a titan of film-making, and I hope that in time, he will be spoken of in the same way people speak of Herzog or Bergman or Lynch or the Coens.

Please visit more of my growing retrospective on The Great Directors.

I figure that my enjoyment of DeMille is not on course with many of my more intellectual counterparts, who are quick to dismiss him and his films as bombastic, overblown, hammy, grandiose, and even bigoted. To my mind, this is a case of throwing out the baby with the bathwater: mixing whatever hatred they have towards his politics into a hatred for his films.

I think DeMille is a wildly underrated director, both in terms of style and impact. Given that his primary interest was in entertaining audiences and giving the public what it wanted, he is trashed by the intelligentsia for not making films for them, exploring the deep and dark recesses of the human heart. I think DeMille could have done so if he was interested in doing so. However, I think DeMille had the goal of making films that would last, that would be watched again and again, and he has succeeded.

Think on this: few directors serve as verbs. There's Capraesque, Felliniesque, Spielbergian and Hitchcockian. Add to that one more: a DeMille picture is quickly understood as being above all, a BIG picture, an event. Now, while that epic quality of his pictures, especially in the latter period, has damaged his reputation among elites, the public at large, both during his lifetime and after, still love his movies because they are entertaining.

One thing people forget about Cecil B. DeMille is that he was one of the few directors to have a long career after the transition from silent to sound pictures. Sunset Boulevard had it absolute right: there were three great directors working in silent pictures: D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, and 'Erich Von Stroheim' (he could say Max Mayerling, but we all know whom he was actually referring to). Which one of them was the only one still standing?

It wasn't that DeMille was better than Griffith or Von Stroheim or more talented than them. I'd argue each was a genius in his own way, but it was because DeMille adapted the best of all three of them in two ways. The first was to work with the studio bosses to retain as much artistic control as possible while still understanding that, for all his trappings of director-as-tyrant, he was still an employee.

This point is what killed Von Stroheim. The second was to adapt to the advancing technology and make films the public would want to see. This is what killed Griffith, who was too attached to making old-fashioned films and was never quite able to move on to sound.

DeMille may be unpopular because again and again, he kept going back to the past and especially The Bible for inspiration. His big hit, The King of Kings, took direct quotations from the Gospels to make his biopic of Christ complete with color sequences, which show DeMille had some idea of where the future was heading. He had a great hit not just because the life of Jesus is known by the majority of Americans, but because he took Preston Sturges' advice before Sullivan's Travels: DeMille made a religious film "with a little sex in it".

I doubt Mary Magdalene was Judas Iscariot's lover, but by adding just a hint of decadence, DeMille manipulated audiences by introducing a sense of sin which Christ, in this case cinematically, could absolve. He did it again with the original The Ten Commandments and its remake when the Children of Israel give themselves to wild abandon at the foot of Mount Sinai. He did it once again with Samson and Delilah: that tale of the wanton woman seducing one of the judges of Israel. As any good director knows, DeMille knew how to grab the audience's attention.

Going back to The King of Kings, for all the trashing DeMille gets about not being able to direct actors, I would hold the scene where Christ (H.B. Werner) has a group of children before him. A little girl asks him if he can heal, and He says yes. The little girl promptly holds up her doll and asks Christ to heal her broken arm. Jesus looks a bit embarrassed by this request, but cleverly grants her request in what I think is an especially tender and touching moment.

Yes, there was a religious aspect to DeMille's pictures, and he may have been a devout Christian, rumors of mistresses notwithstanding. I stand by my view that DeMille understood that for a predominantly Christian nation or at least one that is Christian by default, these subjects would get them into theaters. I can't say one way or another, but I think DeMille had very few financial failures, so that's something to be said for his ability to understand an audience.

It wasn't all togas and crosses for DeMille. He could make contemporary films (although one of them, The Godless Girl, seems to mix the sign of the cross with the sign of the times, and the original The Ten Commandments has a 1920's setting mixed with the Exodus story). The one that has been vilified more than any is The Greatest Show on Earth. Few films are hated for winning Best Picture, but almost all of them have at least one defender.

When it comes to The Greatest Show on Earth, I ain't one. I don't think it was the Best Picture nominated in 1952: I think it was The Quiet Man, followed by High Noon, followed by Moulin Rouge, THEN The Greatest Show on Earth, with Ivanhoe bringing up the rear.

I will, however, stand up for The Greatest Show on Earth being great entertainment. Having seen it twice, I think it captures the best of DeMille: telling a small story (the love triangle between the circus manager, the trapeze artist, and her male rival) in a large canvas with both secondary stories (Buttons the clown who never takes his make-up off and the tortured romance between the elephant trainer and his Muse) with lavish production numbers, culminating in an incredible train crash which in 1952 would have been spectacular and even now is still pretty good. In a more formal review for The Greatest Show on Earth, I will speculate as to the myriad of reasons it won Best Picture, but I can't call it a lousy film because I was entertained by it.

Here, and in his final film as a director, the remake of The Ten Commandments, we can see what made Cecil B. DeMille one of the greats in cinema. He knew how to command and control audience emotion: how to excite them, how to entertain them, and how to hold their attention in spite of a very long picture. He understood how to keep a moving picture moving: going from one scene to another by always having something going on.

There is not much stillness in a DeMille film, and in a curious sort of way, modern directors could learn from him. I am aware that most critics masturbate to No Country For Old Men, but without going into too much detail I felt many scenes were endless and dragged on. It might do the Coen Brothers well to watch a DeMille picture to learn how to keep things moving.

As a side note, it's not my fault that The Greatest Show on Earth won. It's not even Cecil B. DeMille's fault that it won. Therefore both the film and its director should not be condemned for winning.

Now, I'd like to address this issue of DeMille being a bigot in his films. This may be a case of people attaching his political conservatism to his films. Yes, DeMille wanted members of the Directors Guild to take loyalty oaths during the McCarthy era, something I think was a terrible mistake. However, in his films there isn't much if any evidence for the charges of bigotry. The Crusades is not a diatribe against Islam but from what I understand remarkably respectful of it, especially for its time. In the remake of The Ten Commandments, he hints that the Princess of Ethiopia and Moses may have romantic interests in each other: pretty daring stuff for 1956. We also should remember that, despite DeMille's support for loyalty oaths, it was DeMille that broke the graylist against Edward G. Robinson and composer Leonard Bernstein by hiring them when no one else would.

In short, Cecil B. DeMille was a far more complex person than his persona hints at, and that applies to his films. I've always felt that the 1923 The Ten Commandments spoke to an era where people were becoming highly aware that their values in the Ten Commandments were slowly becoming subverted by the Jazz Age of speakeasies, gangsters, fast cars and faster women, and the need for speed & greed. The idea of a 'godless tyranny' oppressing the Chosen People and having to fight for their freedom with God on their side might be the story on the screen, but in 1952 with the Cold War in full strength, could it be DeMille was making an allegory of current-day politics wrapped within a Biblical epic? Perhaps DeMille was smarter than the elitist critics give him credit for...

Cecil B. DeMille's influence is still being felt. Steven Spielberg is probably the most DeMille-like director today. He, like DeMille, has a dynamic and almost flawless ability to give people films that above all entertain. Both are craftsmen in film-making, and it's no surprise. Spielberg has been open how The Greatest Show on Earth was a primary influence in his decision to go into directing: a case of one genius influencing another.

Both, curiously, have been criticized for being too popular, for making films that aren't considered deep. I would argue those criticisms of DeMille and Spielberg are wildly off the mark. Each, in their way, is a deeper and stronger director than they've been given credit for.

I find myself in an odd position. I'm one of the few people who is an open Champion of Cecil B. DeMille as a director and filmmaker. I think by and large he made great films, and that a lot of the bashing against him isn't based on the films themselves but on what people think of him personally. I don't care about a performer's politics, though I am always concerned that his/her politics will overshadow their work and advise to keep their political activities to a minimum. I judge the film itself, and when it comes to Cecil B. DeMille, I have yet to be bored by any of them.

I end with this: Cecil B. DeMille is a genius, a titan of film-making, and I hope that in time, he will be spoken of in the same way people speak of Herzog or Bergman or Lynch or the Coens.

Please visit more of my growing retrospective on The Great Directors.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.