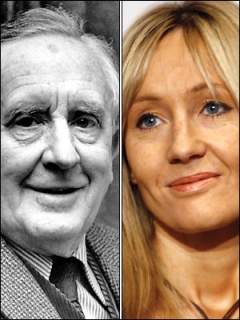

The tale that has been told has taken now the form of legend. Here she is, a woman struggling to make ends meet with a baby to care for. She takes the child in her stroller to the local cafe, where she writes a story about a boy wizard whilst her child sleeps. It reminds me of another story, this of a respected professor who took a blank page from a student's exam and wrote, "In a hole in a ground there lived a hobbit".

Before anyone says anything to the contrary, no, I'm not doubting that's how Joanne Rowling began her Harry Potter series or that it came about in any other way than she has stated. It is an inspirational tale of a woman who had a story to tell, one that children in particular but many adults soon embraced with a fervor and a passion usually reserved for God or the Beatles.

Now, on this All Hallow's Eve, when we celebrate the dark side, I thought it would be good to pause before the release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part I to look over Miss Rowling's work and the films on which they are based. Let me start off by saying two things:

- I am NOT a fan of the Harry Potter books.

- I don't think she is involved in any way, shape, manner or form in witchcraft or Satanic arts, nor does she actively promote such things.

Yes, the books involve Witchcraft (Hogwarts is called the School of Witchcraft and Wizardry) but there is a wild difference between fantasy and those who believe themselves able to summon the forces of darkness. As far as I know, children are able to distinguish between the two, and if they can't, they may end running for Senate. Yet I digress.

I think Rowling just comes from a rather secular background that treats things like Halloween and witches as more comical than dark. It would be interesting to see the post-Potter generation see if they proclaim allegiance to Satan. I doubt they will, instead seeing Potter books as merely fantasy.

However, I look at the books, and I shudder. One of my biggest complaints about Rowling (whom I lovingly call J.K. SPRAWLING) is that the Harry Potter books are so massive they become almost unwieldy. I have read only the first book, and frankly, I never understood why people went overboard in praising it as virtually the Citizen Kane of children's literature.

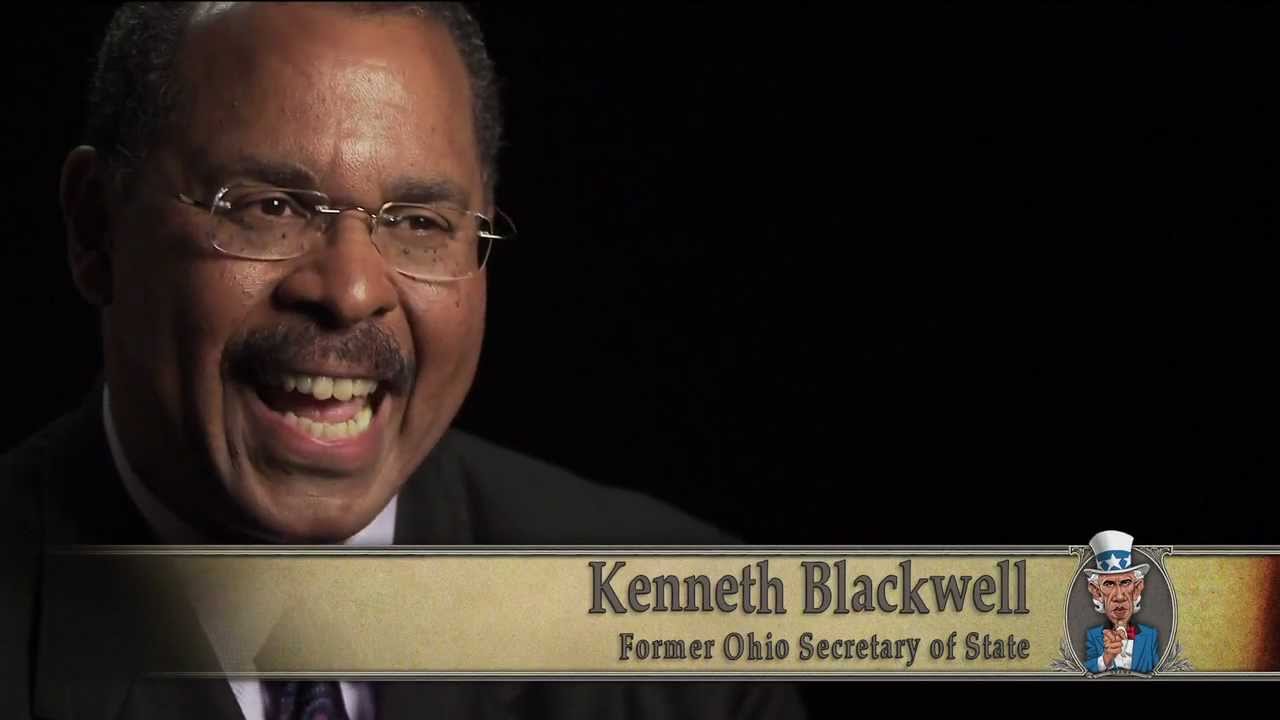

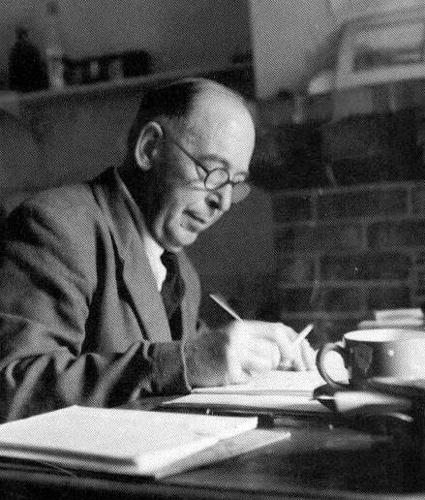

This guy wrote pretty good stuff too, you know.

I don't discount that Rowling could have taken inspiration from C.S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia. Certainly, they have a similar target audience. There are a few differences, however.

I look at my copy of the complete Narnia, and all together, they run a little under 800 pages. 800 pages for a total of seven stories. Rowling also has seven stories, and Deathly Hallows alone runs probably more than 700 pages if not more than 800 pages. In short, Lewis was able to tell a massive story in about the same space where Rowling is able to tell just one part of her massive story.

My biggest issue with Sprawling is length. I simply don't understand why she felt compelled to make her story just so damn long, going into minutiae about everything. How many Quidditch matches does she need to talk about?

My contention has not shifted: the story simply got away from her. What started out as a story about a boy wizard soon became An Epic to dwarf Lewis' Narnia or J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings. It HAD to be big, it HAD to be grand, it HAD to be gigantic. Note that starting from Goblet of Fire, the books themselves have gotten thicker, and thicker, and thicker. As a result, the films have gotten longer, and longer, and longer.

In fact, they've gotten SO LONG that the final book (Deathly Hallows) HAD to be split into two films. There was just no way to compress it into one, at least one that would run about two hours. I can enjoy a long story, but I'm still of the school of "brevity is the soul of wit". I think of some of my favorite books (Call of the Wild, Huckleberry Finn, And Then There Were None) and think they aren't that long.

Therefore, why make Deathly Hallows this book that a child would need both hands to carry? And think, that's just one section of the overall story: there are six others, three of those also rather large. Nothing has convinced me that she couldn't have cut out...a lot.

Of course, I go again to a point: I have read only one book (Philosopher's/Sorcerer's Stone) and didn't care for it. In fact, it discouraged me from reading any other Potter books, not that their massive lengths didn't do a good job of that. Frankly, I never cared to read them, so I've relied on the films. The first two films left me rather unimpressed. In fact, a reason I voted down Chamber of Secrets was because it struck me as basically the same story as Philosopher's Stone.

However, as the story has gotten darker, less cutesy, the films have gotten better. Harry has shifted from this cute boy wizard into a teen in danger from the ultimate evil: Lord Voldemort. At least Harry now has a common theme running through the series rather than just a series of adventures. Overall, I think Rowling is quite intelligent to keep one massive narrative when it would have been easier to create merely a series of smaller ones with the same character.

To her enormous credit (and I hope to be fair) she has created a truly fantastical world for her creations to live in. To validate my view that the longer stories (at least in the films) are not for children anymore, I want to ask my Potter-Heads, whatever happened to Nearly Headless Nick?

I digress to say that another aspect of Sprawling's work that I dislike are the names. You have names like Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, Hermione Granger: not particularly grandiose names but not run-of-the-mill names either. Actually, perhaps with Harry Potter, that would give him a regular 'one of us' style wouldn't it?

As she continued to write, the names got more and more elaborate: Bellatrix Lestrange, Luna Lovegood, Alecto & Amycus Carrow...it really is becoming more and more difficult for me to tolerate. She appears to think the fancier the name the greater it was, while I am of the mindset that simplicity often works best. I further digress to wonder why she is so fond of Deus Ex Machinas in her stories.

Something will almost always turn up at the most opportune moment for Harry to allow him an escape when one was not readily available from his talents or mind. Chamber of Secrets was the worse: Harry had three D.E.M.--the Phoenix, the Phoenix's tears, and the Sword of Gryffindor, all of which magically (no pun intended) show up to save Harry from the memory of Tom Riddle. I call that a cheat.

As we would say, "How convenient".

There is something else, yet another point where Lewis is up on Rowling. Lewis has a wide variety of literature: alongside Narnia, he wrote science-fiction (The Space Trilogy: Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, That Hideous Strength ), romances (Till We Have Faces), and of course, great philosophical works defending The Faith (my personal favorite and a great influence on my life, Mere Christianity). Rowling, on the other hand, has written nothing save Harry Potter stories.

It seems like a trend in modern writing: Stephanie Meyer writes virtually nothing but Twilight and Twilight-related books, James Patterson has Alex Cross and Vince Flynn has MITCH RAPP. Therefore, one can't be too picky about the fact that she hasn't created anything else separate from her creation. However, I long for the days when writers can come up with various stories involving different characters. Granted, one of my favorite writers, Agatha Christie, had many stories with Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, but it should be remembered that one of her best novels (and one of the best novels ever written) had neither: And Then There Were None. For that, I will hold off saying J.K. Rowling is this genius until we see more non-Potter related work.

I intend on giving Deathly Hallows a fair hearing. So far, I think the Potter stories have gotten better and better, and if history is any indication, Deathly Hallows may come close to getting an A (that's the Golden Snitch of rankings, by the way). All decisions will be held off until after viewing.

As for the books, I still cannot find enough interest in going into Hogwarts. I do find Narnia and Middle-Earth a far better place. I may revisit my views after reading all of Rowling's work, but for my taste and my view, she has yet to put a spell on me the way the Inklings have.