BATTLE FOR PLANET OF THE APES

BATTLE FOR PLANET OF THE APESThe Planet of the Apes Retrospective

Primate For Fighting...

Battle for Planet of the Apes was billed as the final chapter of a series that was never intended in the first place...not bad for a one-time film. Battle for Planet of the Apes doesn't appear to have a big budget, but it does have a logic to it that makes the low resources of the film almost forgettable.

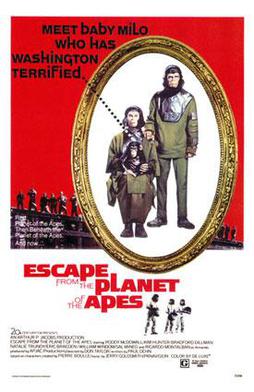

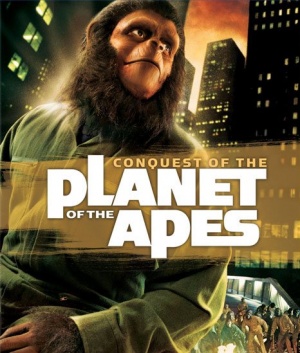

We begin in 2670 A.D. The Lawgiver (John Huston), an orangutan, is telling us the tale of man's fall from power (with clips from both Escape From and Conquest of Planet of The Apes), and then we begin our story.

It is about ten years after the Simian Spring (as I've dubbed the Ape Revolution). Caesar (Roddy McDowall) is Lord over both Beast & Man, with his wife Lisa (Natalie Trundy) and his son and heir, Cornelius (Bobby Porter). The Ape City is relatively peaceful, but it's an uneasy peace. General Aldo (Claude Akins), a gorilla, is itching for the extermination of the humans within, while MacDonald (Austin Stoker), Caesar's right-hand human and brother of the MacDonald who aided the Simian Uprising in Conquest, is not happy that humans are a bit below apes in this benevolent dictatorship.

Caesar tells MacDonald "We are not your masters", and MacDonald retorts, "We are not your equals". MacDonald tells Caesar that the audio and visual tapes of his parents are within the Forbidden City (the one destroyed in the Uprising, not the one in Beijing). Caesar, MacDonald, and the wise orangutan Virgil (Paul Williams) go to the Forbidden City to find them, but not before getting weapons sealed by Mandemus (Lew Ayres), the keeper of the Armory and Caesar's conscious.

Within the Forbidden City, still affected by the nuclear fallout, there are humans who are slowly turning into the mutants from Beneath Planet of the Apes. Their leader is Governor Kolp (Severn Darden), who had been the Inspector that had tortured Caesar in Conquest. Along with his aides Alma (France Nuyen) and Mendez (Paul Stevens), he attempts to rebuild deep within. However, he becomes aware that two apes and a human have infiltrated the city. He orders their capture but the humans fail to capture them. Fearing that this is the final push by his feared and hated nemesis, Kolp decides on a preemptive strike onto Ape City to wipe out the menace once and for all.

Meanwhile, Aldo is planning a coup, with the extinction of the humans as a bonus. Cornelius overhears this but Aldo cuts the limb from under the child before he has a chance to reveal all. Corny is not killed outright but is coming close to it. Caesar, overwhelmed by his son's slow end, is unaware of what either the gorillas or the humans are doing. Kolp is now within striking distance of the apes, and Aldo declares martial law, locking up all the humans in the corral for fear they will aid the invading humans. With Cornelius' death, it is Virgil who forces Caesar to look at what Aldo is doing, but before he can take full charge Kolp attacks. Thus commences the Battle for the Planet of the Apes.

Kolp is routed, but he has given instruction that a doomsday device be used: the Alpha & Omega bomb. It ultimately isn't, with Mendez urging it be almost venerated. Aldo, meantime, wants to kill all the humans, even if it means killing Caesar. However, the first Ape Law is "Ape shall not kill ape", and once they all discover that ape has killed ape; Caesar, filled with rage on learning of how his son died, pursues Aldo into the trees, but Aldo falls trying to attack him.

We end with The Lawgiver telling us it has been 600 years since Caesar's death, and the children he's been telling the story to, ape and human, ask who knows the future. The Lawgiver replies, "Perhaps only the dead", and the statue of Caesar, which has been looking over them all, sheds a single tear.

I think if anything Battle For Planet of the Apes leaves some curious points of logic unanswered. The main events in the film are suppose to be around ten to twelve years after Conquest of Planet of the Apes, but we then wonder how is it that apes acquired the power of speech so quickly. If one looks at things even further, the question arises about Mendez. There was a character named Mendez in Beneath Planet of the Apes, but this obviously couldn't be the same Mendez from Battle (unless radiation has some unknown preservation property). Finally, it is MacDonald who suspects Corny's death wasn't an accident, so how did Virgil come to know the truth?

Moreover, there is a strange inconsistency to Caesar. His goal is to have humans and apes live in harmony, peace, and mutual respect. However, he doesn't appear fazed that he has kept humans out of the Ape City Council. In short, he talks a good game of human-simian relations, but while he may more enlightened than Aldo, both believe humans are not at their level. (It brings to mind someone who believed that apartheid is wrong but accepts the concept of 'separateness' as the natural course of things to where the idea of black or other minority representation in Parliament is just unnatural). For all intents and purposes Caesar is a less-than-likable character: he is a dictator whose word is law. The Ape Council (which has no human representation) apparently is called not to discuss things but to hear Caesar's word.

What John William and Joyce Cooper Corrington do in their script (from Paul Dehn's story) is build on the previous stories while attempting to tie things together. In this respect, they have done an overall good job. The weakest part of Battle may be the fact that the framing device of the Lawgiver. For most of the movie we forget that this is taking place far off into the future. It could have worked better to my view if we just moved into a short history lesson to bring people up to speed, or maybe this story is told in flashback at Caesar's funeral. We could even have a story where apes and humans do live separately, but an older Cornelius and MacDonald's brother seek out a peaceful union while both Aldo and Kolp attempt to gain supremacy on the planet. However, the story that we have on the whole works.

I digress to say that maybe seeing Caesar's statue cry is a touch over-the-top, but it does beg the question: does he cry because he knows the future has not been altered and we will end up in Planet of the Apes, or because he knows humans and apes will be able to live together?

I also was displeased by two clichés in the script. First, why is it that humans (or apes) always die before revealing all they know? Second, one of the mutant warriors was named Sergeant York. Seriously? Sergeant York?

The performances still hold up. McDowall has now reigned as the intelligent chimp, and seeing the agony his son's agony and death bring are moments of strong acting (especially strong given he is in full ape make-up). Darden's Kolp is still the slightly removed and imperious Inspector from Conquest, but his villainy is created in part by the fear and hatred the Simian Uprising and the nuclear destruction brought about him. Of the newer faces, it seems strange that Lew Ayres or John Huston would be so convincing as apes (a credit to the still-impressive make-up work). Ayres has a small role as Mandimus, but he makes the most of being the conscience of Caesar by guarding the Armory (the only one who could speak truth to power, so to speak). Huston's role as the Lawgiver is more like a cameo (given he appears only in the beginning and end) but his distinctive voice keeps our attention.

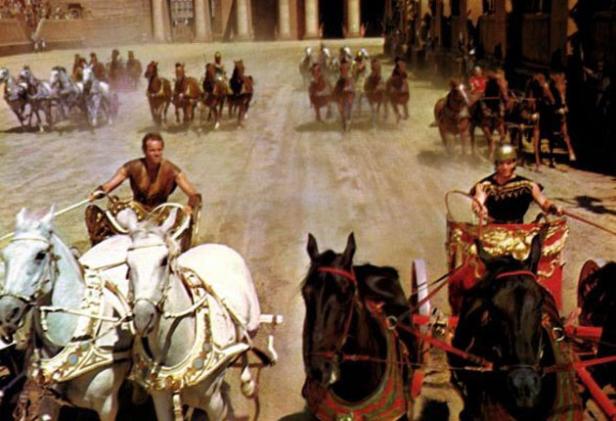

The main flaws in Battle for Planet of the Apes, again, come from a smaller budget. You can see this at certain points: the same treehouses are blown up, the forest at one point looks like a set, and seeing a school bus be part of Kolp's army is a little strange (logical, perhaps, but still might elicit chuckles). However, the battle scenes do have a certain level of excitement (though not as good as one with a really big budget) and we still have a great relevance to the times. The Ape films have been dominated by the theme of how the fear of "the other" has led to tragedy, and here, the fear that humans and simians have (as well as the hatred for them and the idea of how one is the superior species) continues to have hold. I also wondered while watching Battle for Planet of the Apes if there wasn't a hint about our military adventure in Vietnam.

Think on it: a group of humans invade a place that had not attacked them because they feared Simian domination only to find themselves defeated in the forests by subterfuge by the native population.

I also had a strong feeling that Battle for Planet of the Apes addressed (perhaps wittingly but more than likely not) the issue of Internment and a fear of a Fifth Column. Now I know I may be giving both the screenwriters and director J. Lee Thompson more credit than they're do, but when Aldo has all the humans locked away in the corral for fear that they would help the humans against the apes, I thought of how (in one of the most shameful chapters in American history) the Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration had no qualms about locking up American citizens merely because they were of Japanese ancestry and feared they would (or were) working for the Emperor against the U.S.

On the whole, Battle for Planet of the Apes suffers from a lack of money (the results of which are on the screen). However, the story it told keeps our attention and still has something to tell us about the importance of mutual respect for those who are not like us, and the fear that xenophobia can unleash. On that front, the battle goes on.

DECISION: B-

Next Planet of the Apes Film: Planet of the Apes (2001)

.jpg)