BEN-HUR (1959)

Our Chariots Await...

In an age where epic films were all the rage, few can hold themselves to Ben-Hur's equal. It isn't just in the grandness, the vastness of the film itself. It is also that, unlike other big films, there is a real personal story within Ben-Hur, a human drama that, stripped of its more grand features, is remarkably intimate.

While I know today sprawling films like Ben-Hur are distrusted, even dismissed because of their sheer size, when watching the film one is struck at the intelligence behind it, the themes it touches on, and putting the spectacle aside, what a remarkably deep film Ben-Hur actually is. At heart, Ben-Hur is a story about freedom: physical and spiritual, forgiveness versus vengeance, and the cost of staying true to yourself. It also has one of the greatest action sequences in film history.

In an age where epic films were all the rage, few can hold themselves to Ben-Hur's equal. It isn't just in the grandness, the vastness of the film itself. It is also that, unlike other big films, there is a real personal story within Ben-Hur, a human drama that, stripped of its more grand features, is remarkably intimate.

While I know today sprawling films like Ben-Hur are distrusted, even dismissed because of their sheer size, when watching the film one is struck at the intelligence behind it, the themes it touches on, and putting the spectacle aside, what a remarkably deep film Ben-Hur actually is. At heart, Ben-Hur is a story about freedom: physical and spiritual, forgiveness versus vengeance, and the cost of staying true to yourself. It also has one of the greatest action sequences in film history.

It is around the time of Christ, when the land known as Judea is under Roman occupation. Messala (Stephen Boyd) is the new Roman commander in Jerusalem. He is not a stranger to the land, having spent his youth there. He had an extremely close friend there: a Jewish prince, Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston). Judah is thrilled to see his old friend back, but in the ensuing years their views have altered them: Messala believes in Roman supremacy over the Earth while Judah strongly believes the Jewish people should be free. Messala wants Judah to collaborate with him and give him the names of Jews opposed to Roman rule. Judah refuses. Thus, they that were once the deepest of friends turn into the bitterest of enemies.

On the arrival of the new Governor of Judea, Judah's sister Tirzah (Cathy O'Donnell) accidentally causes tiles from their palace to fall on him. She, along with Judah and their mother Miriam (Martha Scott) are arrested. Messala, knowing they are innocent, decides to take revenge by condemning Judah to a slave ship and the women to imprisonment. Judah attempts escape and nearly kills Messala, but cannot do it. Thus, it's off to the galleys.

While as a slave, Judah comes into contact with Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), a Consul of the Empire. In an epic battle, Judah saves Arrius' life and both fall overboard. A Roman ship rescues them, and a grateful Arrius not only sees to Judah's freedom but adopts him as his son.

Judah now is with the cream of Roman society, meeting all kinds of important people, including the new Governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate (Frank Thring). Still, Judah seeks vengeance against Messala and a return to his homeland, to his family, and to Esther (Haya Harareet), the beautiful daughter of the Hur family servant Simonides (Sam Jaffe). Arrius reluctantly allows him leave to return.

Judah now is with the cream of Roman society, meeting all kinds of important people, including the new Governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate (Frank Thring). Still, Judah seeks vengeance against Messala and a return to his homeland, to his family, and to Esther (Haya Harareet), the beautiful daughter of the Hur family servant Simonides (Sam Jaffe). Arrius reluctantly allows him leave to return.

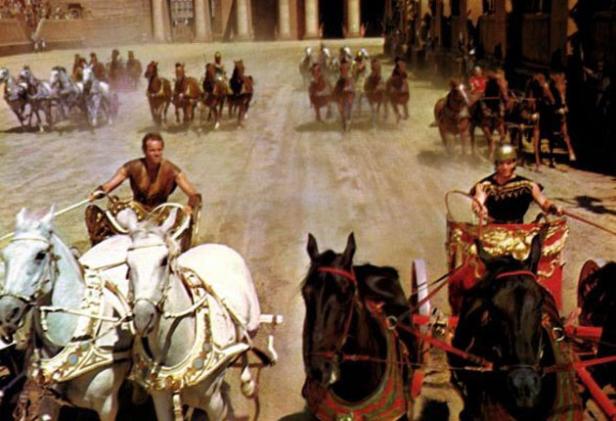

One in Judea, he comes across Balthasar (Findlay Currie), a wise man from the East who is searching for a man whom he once brought gifts to as a child. Balthasar is staying with Sheik Ilderim (Hugh Griffith), a rich Arab whose main ambition is to race his chariot against the greatest charioteer in Judea, one Messala. Judah's reputation as a charioteer preceeds him, and he sees this as his chance to take revenge (and also sets up one of the most iconic moments in film history). They race, Judah wins, Messala is crushed (literally), but Judah learns what both Esther and Messala know: Tirzah and Miriam are now in the Valley of Lepers.

Judah's revenge is still unsatisfied, but Esther has turned to the teachings of a young rabbi, who teaches that one should "love your enemy and do good to those who harm you". Judah will hear none of this, and he is determined to bring his family out of the Valley. He does so, with a hope that the young rabbi may cure them. However, the group arrives in Jerusalem just as Pontius Pilate is condemning the Teacher to death. Upon the Cross, they look in sorrow. However, after the storm that strikes Jerusalem upon the Teacher's death, there is healing and ultimately forgiveness in the House of Hur.

In truth, you can reduce all of Ben-Hur to three lines: A Prince who became a Slave, a Slave who became a Charioteer, a Charioteer who defied an Empire.

Director William Wyler made two jokes about Ben-Hur. One, that he wanted to see if he could make a Cecil B. DeMille picture, and two, that it took a Jew to make a good film about Jesus. He wasn't kidding on either count. Wyler kept the film moving so brilliantly that one never notices how long Ben-Hur is: an astonishing three and a half hours long (not counting overture and entre'act). However, nothing in Ben-Hur ever appears gratuitous or unimportant, especially considering how Wyler managed to combine the spectacle with the intimate. He not only managed to do that, but to connect the story of Judah with that of Christ, almost having them parallel each other. Wyler had the main story (that of Judah Ben-Hur) as well as that of Christ. In Wyler's genius, he brought in characters from both their lives in the film to let us know that eventually Judah and Jesus would meet more than once.

For example, in the prologue we have the Presentation of the Magi to the Christ Child. Among them is Balthasar. Once we get to where Judah returns to Judea, we see Balthasar again. Thus, we know that the story of Christ will keep coming into contact with that of Judah. We should already know this because from time to time in Ben-Hur, we see the idea of Yeshua Ben-Yosef (though we never see His face or hear His voice). Instead, soft organ music plays when His presence is on screen. Judah and Christ had already come into contact when the former is being led to the galley ships. In an unnamed town, Judah is desperate for water but the Romans are under orders to deny him. In his despair, Judah begs God to help. At this point, we hear the soft music and a hand that brings him water.

In this moving scene, it is Wyler's direction that is at the height of its power. The Roman commands this man to stop giving Judah water and the strange figure rises quickly. Without seeing the stranger's face, the Roman soon starts to back away, on occasion turning to look at Him with a strange mixture of fear and awe. We in the audience know the stranger is suppose to be Christ, and thus we can understand the Roman's reaction, but it is Wyler who directs the scene so well. If one looks at it, there are no strong words, there are no strong actions other than Jesus rising quickly from the ground. Yet we still feel the emotional impact of this pagan coming into contact with the Christ.

Wyler's direction of people is brilliant throughout Ben-Hur, and is even more impressive given the variety of emotions the film goes through. There are moments of intense action (the sea battle and the legendary chariot race), but there are also moments of intimacy. Take the love story between Judah and Esther. Here, Wyler directs the lovers to be gentle towards each other, even perhaps a bit hesitant. The same goes for when Miriam and Tirzah go back to their home after their release. Only Esther knows they are alive, but Wyler does not show the effects of leprosy on the Hur women. This is all done by suggestion: the lighting (or lack thereof), keeping them in the shadows, the reaction in Esther's face to what she has discovered. We even have moments of comedy through Sheik Ilderim, a lusty man who loves his horses and is a general bon vivant.

Ben-Hur manages to sweep you into both its grandness and its intimacy, and William Wyler is the central force in that. He directed all his actors so well, and their performances in the film are some of the best in their careers. Heston, curiously, was not the first choice to play Judah Ben-Hur, but now it doesn't seem possible that anyone else could have done it. He is imposing in the action scenes (as he usually is), but in the love scenes between him and Harareet he shows a remarkable tenderness that he isn't known for. One of his best scenes is actually not the chariot race, but right after. He comes to a dying Messala and realizes that even while he has defeated his bitter enemy, he still has not found the peace he expected from his revenge. He goes into the now-empty racetrack, aware of his hollow victory. It is a beautiful scene.

Credit should also go to Boyd's Messala, a man who we see evolve from a good friend into a bitter enemy. A good actor understands that a villain never sees himself as a villain, and Messala doesn't see himself as evil but as a Roman on the make. If it means getting even with a former friend and member of high Judean society to teach the population a lesson, so be it. Griffith is also a delight as the Sheik who persuades Judah that by running in the chariot race he can stamp the arrogance of the Romans--to be defeated by a Jew is a thought too rich for him to pass up (side note: it is nice to see a film where Arab and Jew work together, and where they show respect to each other). Even the smaller parts: Jaffe's loyal servant and Currie's Wise Man, add to the great performances. Harareet perhaps is a bit too gentle as Esther, but her scenes with Heston are done so well that you believe they have loved each other for a long time.

There is an element in Ben-Hur that I have not mentioned but that without it the film would not be as brilliant as it is. That is Miklos Rozsa's score: among the greatest ever made for motion pictures. Again and again, it is Rozsa's score that sells every scene where music is heard: starting from the very beginning where we see the Presentation of the Magi (where the music enhances the gentleness of the birth of the Christ Child as well as reverence for this monumental event) and then to the gigantic opening music where we know THIS will be an epic, right down to the love theme between Judah and Esther, the battle on the sea, the rowing music, the triumphant arrival into Rome, the ghastly horror of Miriam and Tirzah's leprosy and the restoration of the Hur family. Few scores have captured both the grandness and intimacy of a story, but Miklos Rozsa's music for Ben-Hur does it so well and so consistently that we must marvel at just how one film score can be as powerful and overwhelming as the movie itself.

Curiously, the one major scene in Ben-Hur that does not have music is perhaps the most legendary scene in the film (and one of the most legendary in film history): the epic chariot race. The film has been building up to this moment, not just in terms of action but in terms of story: the fierce rivals will finally confront each other. By this time into Ben-Hur, we know everything there is to know about the characters, their motivations, and their goals. Once we start the race, we get a thrilling sequence that moves (in every sense of the word). Wyler gets the camera close to the action, and we get brilliant stunt work under the direction of Yakima Canutt. In those ten minutes or so the race never lets up and the audience is completely caught up in the excitement and terror of this battle between Judah and Messala. The best compliment that could be given to the chariot race is that it was all done live: no great technical tricks, few stunt doubles, so the scene becomes thoroughly real.

As much as Ben-Hur has great action scenes, it also has a compelling personal story. It is about ideas: in fact, Messala tells Judah early in the film, "How do you fight an idea?" The idea of staying true to your principles and to yourself (note that Judah was a secular Jew and later had no problem dressing as a Roman but at heart his loyalty still lay with his people), how truly an occupier and the occupied cannot be friends so long as one holds himself master and the other slave. We also have the themes of revenge versus redemption, best captured between the two Judean princes (one of the House of Hur, the other of the House of David), of two Jewish freedom fighters (one political, one spiritual), one who wins a Crown of Laurels, the other a Crown of Thorns. The brilliance of Ben-Hur isn't just with the action (although those in themselves make it brilliant), but also that the film is highly intelligent in how it deals with the ideas of love, revenge, justice, and mercy.

There are other things to mention. All the elements in Ben-Hur work: Elizabeth Haffenden's costumes (from the simplicity of Christ's robes through the grand Roman robes), the sets by Edward Carfagno, William A. Horning, and Hugh Hunt, and Robert L. Surtees' brilliant cinematography. If there's anything I would object to, it is Griffith's frightful make-up work: not only is it excessively dark, but you can tell where they stopped making him up. However, that's really a tiny complaint to a brilliant film like Ben-Hur.

Finally, I'd like to address the point of any gay subtext in Ben-Hur. Gore Vidal (who did not receive credit for his work on the screenplay) insists that there was a gay subtext between Messala and Judah and that it was Judah's 'rejection' of Messala that turned him into a villain. After having seen the film, more than once, whatever gay subtext there might be is thoroughly lost on me. If one wants to read that in the film, they are free to do so. I did not see it and am puzzled as to why Gore Vidal insists there is one.

What Ben-Hur is in the long run is an intimate epic (which is not an oxymoron). We have the vastness of the story as well as at its core a human story about forgiveness in spite of terrible things. It is truly an epic film about ideas. A great film that still thrills, Ben-Hur simply runs away with it.

1960 Best Picture: The Apartment

There are more Best Picture reviews as well as Essentials.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.