Casbah Conflict...

I always bristle when people tell me that 'it's just a movie'. It isn't that I should take everything in a movie seriously. However, I reject the idea that a movie can't have an impact on people because I've seen for myself just how a film, if done correctly, can shift attitudes to manipulate an audience.

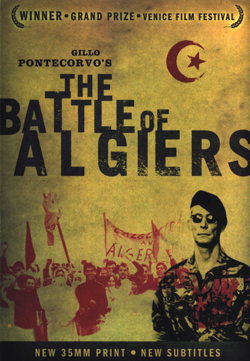

The idea that a mere movie cannot have a powerful impact on an audience is a false one, and the definitive case against that is The Battle of Algiers. Is it art? Is it propaganda? Is it just a movie? I think in fact, The Battle of Algiers is a brilliant example of how a movie can be so strong visually that one becomes part of the story, though not sometimes for the good.

I always bristle when people tell me that 'it's just a movie'. It isn't that I should take everything in a movie seriously. However, I reject the idea that a movie can't have an impact on people because I've seen for myself just how a film, if done correctly, can shift attitudes to manipulate an audience.

The idea that a mere movie cannot have a powerful impact on an audience is a false one, and the definitive case against that is The Battle of Algiers. Is it art? Is it propaganda? Is it just a movie? I think in fact, The Battle of Algiers is a brilliant example of how a movie can be so strong visually that one becomes part of the story, though not sometimes for the good.

The Battle of Algiers tells the story of the final few years of the French occupation of Algeria. Long a part of their empire, after World War II the native Algerians start demanding independence, but after being thrown out of French Indochina (now Vietnam), the French aren't willing to give up another bit of the realm, at least, not without a fight. Unfortunately, they get one, and a particularly brutal one where both the French and the Algerians commit horrifying acts of murder that only cause the sides to dig in deeper, and bring misery to non-combatants.

We begin with an old Algerian, who has obviously been tortured, revealing the hideout of four agents of the FLN (National Liberation Front). The French army surrounds them, and of those trapped, including a woman and a child, only one stares out in stern defiance. That would be Ali La Ponte (Brahim Haggiag), a native Algerian. We go back three years earlier, to 1954. Ali is a petty street criminal who is imprisoned, more than likely because among other things, he dared strike back at a European. While in prison, he witnesses an execution of an FLN member and becomes radicalized to join the cause. Once out, he quickly rises through the ranks to become a leader, albeit a hotheaded one.

The FNL continues their harassment of the French living within Algiers, while the French strike back by requiring indignities of the Arabs in their own country, ranging from checkpoints around the Casbah and requiring the Algerians to carry identification papers at all times to searching them at will. The fight between the FNL and the French grows, with more and more barbaric acts: two brutal bombings that are shocking in and of themselves but also by how freely both sides appear to kill those not actually doing the fighting. The city of Algiers is a city besieged, where fear and paranoia grip both populations. Finally, the French paratroopers are brought in, led by Colonel Mathieu (Jean Martin).

The Colonel is efficient in his efforts to quash the insurrection/rebellion due to his response to a planned general strike by the Algerians. His plan to root out the leadership, Operation Champagne, bears results, but again at a particularly brutal cost. Eventually, Colonel Mathieu has cornered Ali and his compatriots, and after given warning to come out, the four of them choose death before surrender.

In a coda, we see the uprising has not quieted down. Instead, a fiercer one has emerged. On December 21, 1960, the last day of demonstrations that take place after the main events of The Battle of Algiers, a voice calls out to the unseen demonstrators, asking what they want. The response comes out clear: "Freedom! Independence!"

The film ends with women waving the Algerian flags in a frenzy of fury, a dance of defiance to where they will not stop until they get what they want. A voice-over tells us that on July 2, 1962, Algeria at last gains independence.

In a coda, we see the uprising has not quieted down. Instead, a fiercer one has emerged. On December 21, 1960, the last day of demonstrations that take place after the main events of The Battle of Algiers, a voice calls out to the unseen demonstrators, asking what they want. The response comes out clear: "Freedom! Independence!"

The film ends with women waving the Algerian flags in a frenzy of fury, a dance of defiance to where they will not stop until they get what they want. A voice-over tells us that on July 2, 1962, Algeria at last gains independence.

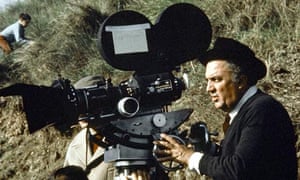

The Battle of Algiers' brilliance comes from many fronts (no pun intended). Chief among them is Marcello Gatti's cinematography. Although everything in The Battle of Algiers was filmed specifically for the film, the look of the film is one that could easily pass for a documentary. This director Gillo Pontocorvo accomplished first by filming in black-and-white and second by the brilliant camera work. Pontocorvo does not have exaggerated angles or shots that draw attention to themselves. Instead, he shows things as they would have happened.

Take for example when the paratroopers come marching into Algiers. The angles are from the street, sometimes from the feet of the marching soldiers, which gives us a feeling that the footage was gathered from a newsreel as opposed from a professional film crew. Other examples are from when either bombings take place (from the French coming into the Casbah, or the FLN going to the European quarter).

Another brilliant element within The Battle of Algiers is Ennio Morricone's score. Every time his music appears, it enhances the scene and makes it far more powerful. We start from the first note, where the music signals chaos and fierce fighting, right down to the music when the bodies have to be pulled from the wreckage. In these moments, the score is exceptionally sad, mournful, and in a stroke of brilliance, it is the same music repeated over both when the Algerians and the French are killed.

Here, Pontecorvo subliminally signals to us that death is death regardless of who it has struck.

Side note: I found it ironic that the song the French teens about to be bombed were listening to was a Spanish song with the refrain "Hasta mañana, Rebecca", (Until tomorrow, Rebecca), when we the audience know that for some of them, there will be no tomorrow. The scene when the Algerian women are about to set off to do their act of terror is set to the tense beating of native drums, which only enhances the tension of the sequence.

Here, Pontecorvo subliminally signals to us that death is death regardless of who it has struck.

Side note: I found it ironic that the song the French teens about to be bombed were listening to was a Spanish song with the refrain "Hasta mañana, Rebecca", (Until tomorrow, Rebecca), when we the audience know that for some of them, there will be no tomorrow. The scene when the Algerian women are about to set off to do their act of terror is set to the tense beating of native drums, which only enhances the tension of the sequence.

We must also point out to the performances. All the actors in The Battle of Algiers are non-professionals and with FNL leader Saadi Yacef playing a fictionalized version of himself called Jaffar, with the exception of Martin as Col. Mathieu. It would have been easy to paint the Algerians as heroic and the French as villainous, but Pontecorvo does not make things easy for the viewer.

Mathieu is not portrayed as a monster but as an efficient military man given a task and doing it to the best of his ability. At a press conference he tells the reports the truth: that the conflict they are in boils down to one thing: "the FNL wants to throw us out of Algeria and we want to stay". What he thinks of it is immaterial.

Mathieu is not portrayed as a monster but as an efficient military man given a task and doing it to the best of his ability. At a press conference he tells the reports the truth: that the conflict they are in boils down to one thing: "the FNL wants to throw us out of Algeria and we want to stay". What he thinks of it is immaterial.

In the same vein, Yacef/Jaffar is not portrayed as a barbarian bent on killing every Frenchman he can lay his hands on. On the contrary, he realizes the truth about terror as a weapon: "Acts of violence don't win wars. Neither wars nor revolutions. Terrorism is useful as a start, but then, the people themselves must act".

Even for a film about revolution such as The Battle of Algiers, where the temptation to make the FNL and their supporters heroic is strong, Pontecorvo allows moments of barbarity to seep in. For example, we hear a voice-over making the newest pronouncements from the FNL about living a more Islamic life. Among the proclamations is a death sentence for those who are drunk. While the voice-over continues, we see a group of children harassing an old drunk, making look like a miniature mob. It is a remarkably terrifying and sad scene.

Even for a film about revolution such as The Battle of Algiers, where the temptation to make the FNL and their supporters heroic is strong, Pontecorvo allows moments of barbarity to seep in. For example, we hear a voice-over making the newest pronouncements from the FNL about living a more Islamic life. Among the proclamations is a death sentence for those who are drunk. While the voice-over continues, we see a group of children harassing an old drunk, making look like a miniature mob. It is a remarkably terrifying and sad scene.

The emotional impact of The Battle of Algiers is still so powerful, so real, that watching it may make one almost sympathetic to violent overthrows of governments. It is no accident that it looks like a documentary. It is no accident that it takes a strong point of view. I confess that after watching it for the first time, I got so caught up in its emotion that if I had been asked to right then and there, I would have been tempted to join the resistance against French occupation, and I'm one of the most socially conservative, bourgeois individuals I know.

The Battle of Algiers is still relevant today: in the anger of occupation, the stubbornness of combatants, and now with the rise of the Arab Spring a willingness of the man and woman on the street to continue fighting and dying for freedom.

Is it propaganda? Yes. Is it art? Yes. Is it just a movie? Yes and no.

The Battle of Algiers is a thrilling and powerful film, with an emotional impact that will stay with you long after you finish it. For a film to do that, even after nearly fifty years, is a sign that the battle goes on.

The Battle of Algiers is still relevant today: in the anger of occupation, the stubbornness of combatants, and now with the rise of the Arab Spring a willingness of the man and woman on the street to continue fighting and dying for freedom.

Is it propaganda? Yes. Is it art? Yes. Is it just a movie? Yes and no.

The Battle of Algiers is a thrilling and powerful film, with an emotional impact that will stay with you long after you finish it. For a film to do that, even after nearly fifty years, is a sign that the battle goes on.