THE KING'S SPEECH

THE KING'S SPEECH

Vox Vocis De Rex Imperator...

Under the British Constitution, the Sovereign is the Head of State, and all temporal power rests upon him/her. All governments serve at his/her leisure, all naval ships are his/hers, even the postal service is the Royal Mail. As such, he/she should project those qualities known as 'majesty', 'power', 'dignity'. You wouldn't therefore, make a shy, insecure, almost frightened stammerer By The Grace of God, of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions Beyond the Seas, King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India.

That being the case, Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, Duke of York, would be a lousy candidate. Even worse, said Duke, better known as Bertie, knows it. If he is to rise to the man he is needed to be, he needs the love of a strong woman. Check. He also needs a good speech therapist. Double Check.

The King's Speech, based on how this shy man thrust onto the monarchy joined with a cheeky but frustrated Australian actor to bolster the British spirit at the onset of the Second World War, is a well-crafted, elegant tale of a most unlikely friendship.

Under the British Constitution, the Sovereign is the Head of State, and all temporal power rests upon him/her. All governments serve at his/her leisure, all naval ships are his/hers, even the postal service is the Royal Mail. As such, he/she should project those qualities known as 'majesty', 'power', 'dignity'. You wouldn't therefore, make a shy, insecure, almost frightened stammerer By The Grace of God, of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions Beyond the Seas, King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India.

That being the case, Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, Duke of York, would be a lousy candidate. Even worse, said Duke, better known as Bertie, knows it. If he is to rise to the man he is needed to be, he needs the love of a strong woman. Check. He also needs a good speech therapist. Double Check.

The King's Speech, based on how this shy man thrust onto the monarchy joined with a cheeky but frustrated Australian actor to bolster the British spirit at the onset of the Second World War, is a well-crafted, elegant tale of a most unlikely friendship.

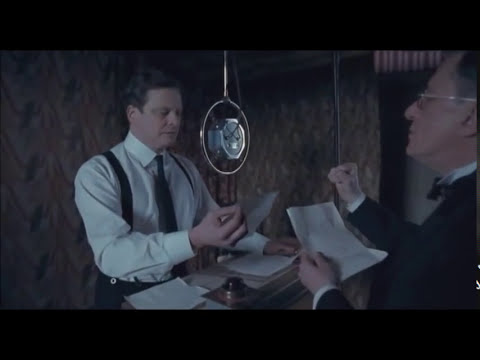

Bertie (Colin Firth) has had this stammer ever since he could remember. Even the shortest and most mundane of public speaking engagements bring terror to him, which only exasperates his impediment. While his wife Elizabeth (Helena Bonham Carter) is supportive, she, who was not born Royal, cannot give the speeches for him. Bertie's difficulties and insecurities are an increasing burden on him, and in desperation HRH the Duchess of York seeks out Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), an eccentric speech therapist outside established circles after exhausting all other options for a cure or treatment for Bertie's stammer.

Lionel agrees to see HRH the Duke, but there are conditions to his sessions. First, they must come to him in his consulting room. Second, and perhaps more outrageously, Lionel insists on referring to his patient as 'Bertie' rather than His Royal Highness. This irks the Duke, but he agrees to it. Lionel is convinced the stammer is psychologically-based, but the Duke isn't about to delve into personal matters with a commoner, let alone an Australian at that. They agree to try just basic physical techniques, and they do have some success.

Lionel agrees to see HRH the Duke, but there are conditions to his sessions. First, they must come to him in his consulting room. Second, and perhaps more outrageously, Lionel insists on referring to his patient as 'Bertie' rather than His Royal Highness. This irks the Duke, but he agrees to it. Lionel is convinced the stammer is psychologically-based, but the Duke isn't about to delve into personal matters with a commoner, let alone an Australian at that. They agree to try just basic physical techniques, and they do have some success.

As he improves his speech, his father, King George V (Michael Gambon), is concerned about his elder son Edward, Prince of Wales (Guy Pierce), known to the family as David. The Heir to the Throne is besotted by his newest mistress, one Mrs. Simpson (Eve Best). In short time, King George dies, and the throne is inherited by David, now known as Edward VIII.

However, since David is unmarried and childless, Bertie is now Heir to the Throne. The prospect of becoming King terrifies Bertie, even more so when Edward VIII abdicates the Throne to marry Mrs. Simpson. The anxiety of the Abdication Crisis is a cause of the break between Bertie and Logue, and at the end of the Crisis, Bertie finds himself in the position he does not want: King-Emperor. He finds himself overwhelmed to the point of collapse, with his stammer returning to full force. The now-Queen Elizabeth gently gets Bertie and Lionel to reconcile, and the therapist begins to work to get him through the Coronation and then, when war is declared with Nazi Germany, The King's Speech upon entering World War II.

However, since David is unmarried and childless, Bertie is now Heir to the Throne. The prospect of becoming King terrifies Bertie, even more so when Edward VIII abdicates the Throne to marry Mrs. Simpson. The anxiety of the Abdication Crisis is a cause of the break between Bertie and Logue, and at the end of the Crisis, Bertie finds himself in the position he does not want: King-Emperor. He finds himself overwhelmed to the point of collapse, with his stammer returning to full force. The now-Queen Elizabeth gently gets Bertie and Lionel to reconcile, and the therapist begins to work to get him through the Coronation and then, when war is declared with Nazi Germany, The King's Speech upon entering World War II.

We can debate the historic accuracy of The King's Speech, but since I've long argued that films are not history lessons, we can forgive any inaccuracies in David Seidler's script. Instead, the film deals with two men, thwarted in their own way (Bertie a reluctant monarch, Lionel a failed actor), who in spite of themselves find a friendship that transcends barriers of status, position, and emotion.

The heart of The King's Speech is Firth's performance as the future George VI. In the very first scene, when he has to address an audience, he already registers fear and a deep reluctance to speak. Seeing his agony and frustration when he finally begins to try to speak is heartbreaking for the audience. Considering that he has yet to speak a line of dialogue apart from the prepared speech, is a sign of Firth's talent that he communicates so much with his face and body.

Throughout The King's Speech, Firth never draws attention to the stammer. Instead, it appears to be part of who he is, and when we see him slowly making strides to lessen it we cheer him on since we get to know just how bullied he was by his father and brother. We see this when the future Edward VIII tells Bertie his plans to marry Mrs. Simpson.

The look of horror overwhelms him, not just because he's appalled that his brother/King would marry such an unacceptable woman but because he knows it will force him to be King. Trying to explain this to David brings an intense attack of stuttering. David gives him a look of contempt, and begins mocking him as he did when they were children. Here again, it's difficult to see someone we've come to know as a decent but troubled man be pushed down so hard by his own family.

Throughout The King's Speech, Firth never draws attention to the stammer. Instead, it appears to be part of who he is, and when we see him slowly making strides to lessen it we cheer him on since we get to know just how bullied he was by his father and brother. We see this when the future Edward VIII tells Bertie his plans to marry Mrs. Simpson.

The look of horror overwhelms him, not just because he's appalled that his brother/King would marry such an unacceptable woman but because he knows it will force him to be King. Trying to explain this to David brings an intense attack of stuttering. David gives him a look of contempt, and begins mocking him as he did when they were children. Here again, it's difficult to see someone we've come to know as a decent but troubled man be pushed down so hard by his own family.

When one is in need for kooky Australian, you call upon Geoffrey Rush, and in The King's Speech, he is another real-life kooky Australian. He makes him a bit comical, but Lionel Logue isn't someone we laugh at but laugh with. We delight in his cheeky demeanor, being as deferential to HRH the Duke of York as required publicly, but treating him as an ordinary person in private.

His Lionel is confident in his abilities and treats Bertie as just another man, which does bother the Duke but which also allows him to open up as he hasn't before to anyone save the Duchess. Lionel, however, has his moments when he deals with his home life, which refreshingly is void of great drama. Instead, his home is filled generally with love among his wife and sons.

His Lionel is confident in his abilities and treats Bertie as just another man, which does bother the Duke but which also allows him to open up as he hasn't before to anyone save the Duchess. Lionel, however, has his moments when he deals with his home life, which refreshingly is void of great drama. Instead, his home is filled generally with love among his wife and sons.

Both Firth and Rush work so seamlessly when they're together on screen. When George V has died, one of the first people he sees is Lionel. In between Lionel giving the Heir to the Throne rather odd instructions on how to get what he wants to say out (such as singing his words to Swanee River), the Duke reflects somewhat on his childhood, one filled with abuse, a sense of worthlessness in spite his royal birth, and the death of a younger brother. In other films, we might have had this flashback visualized, but in The King's Speech, it's just Firth and Rush, conversing, the sadness of both men evident.

It's all quite subtle, but here, the audience, if not the participants, realize that, for better or worse, Lionel Logue is the closest thing to a friend HRH The Duke of York has.

It's all quite subtle, but here, the audience, if not the participants, realize that, for better or worse, Lionel Logue is the closest thing to a friend HRH The Duke of York has.

We can't leave out Bonham Carter's performance as the future Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. Her role is actually rather small, but she really stands out in her scenes with both Rush and Firth, and even more so in the one scene that doesn't involve them. Mrs. Myrtle Logue (Jennifer Ehle), who is unaware of whom her husband has been treating, arrives earlier than expected when the King and Queen call on Lionel. She walks in and is understandably shocked on discovering the Queen Empress in her dining room. Without missing a beat, Elizabeth rises from her chair and informs her that the proper way to address her is "Your Majesty" the first time, "Ma'am" after that, adding it's "ma'am" as in "ham" and not "ma'am" as in "palm".

She does this with the air of a woman who realizes it all may sound a bit silly but it is the right thing to do. In this brief scene she shows Queen Elizabeth to be both the regal and informal, a mix of being both a Queen and a straightforward Scottish girl. It added a bit of light comedic touch.

She does this with the air of a woman who realizes it all may sound a bit silly but it is the right thing to do. In this brief scene she shows Queen Elizabeth to be both the regal and informal, a mix of being both a Queen and a straightforward Scottish girl. It added a bit of light comedic touch.

Finally, in even smaller parts, Gambon as King George V and Pearce as Edward VIII showed they didn't need to be the center of attention to draw said attention. Gambon not only physically resembles King George V but also manages to communicate his bullying manner mixed with whatever love and pride for his second son he could muster. Pearce displayed the future Duke of Windsor's rapt devotion to Mrs. Simpson, going so far as to think what his ascendancy to the Throne would mean for her. He is clearly under her command, and Pearce shows us just how controlled he was by this twice-divorced American.

All these performances are drawn out by Tom Hooper's direction. Hooper creates genuine tension in The King's Speech when we come to that climatic moment when he has to speak to his people on the day war is declared. Placing Firth in front of us, we have him and Rush together in the broadcast booth, and with the second movement of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony underscoring the scene, we see Lionel guide The King as if he were a conductor at a concert.

Hooper builds the tension by having us see the King start to falter, and those few moments of silence are made longer by the tension of whether or not he can get through this intense and frightening moment for him. At the end of it, Lionel chastises the King slightly for still stuttering on the "w"s. The King, somewhat humorously, replies something to the effect that it was done so that people will know it was actually him.

Hooper builds the tension by having us see the King start to falter, and those few moments of silence are made longer by the tension of whether or not he can get through this intense and frightening moment for him. At the end of it, Lionel chastises the King slightly for still stuttering on the "w"s. The King, somewhat humorously, replies something to the effect that it was done so that people will know it was actually him.

Near the beginning of The King's Speech, Lionel gets the Duke to attempt to recite Hamlet's To Be or Not To Be soliloquy onto a record. He blocks the Duke's ability to hear himself speak via loud music he plays into headphones Lionel places on him. One can easily guess what will be the end results, but it doesn't take away from that moment when both the Duke and Duchess realize what exactly they are hearing.

The King's Speech is more than a historic drama. It really is about a man facing his fears and dealing with them because it has to be done. It speaks to personal courage, even when one doesn't believe in himself. During the worse of the Blitz, on one of their tours of the devasted London, a person cheered their sovereign by exclaiming, "Thank God for a Good King". Without missing a beat, King George VI responded, "Thank God for a Good People".

On the surface, this shy, insecure, almost frightened stammerer would not be a good choice for King. History, however, showed he was perfect for the role.

On the surface, this shy, insecure, almost frightened stammerer would not be a good choice for King. History, however, showed he was perfect for the role.

|

| Lionel Logue 1880-1953 |

|

| Their Majesties King George VI: 1895-1952 Queen Elizabeth: 1900-2002 |

2011 Best Picture: The Artist

Post Script: Since writing this review The King's Speech has won Best Picture. As such, I have included reviews for other Best Picture Winners as part of my continued efforts to review every winner from 1928 to today.