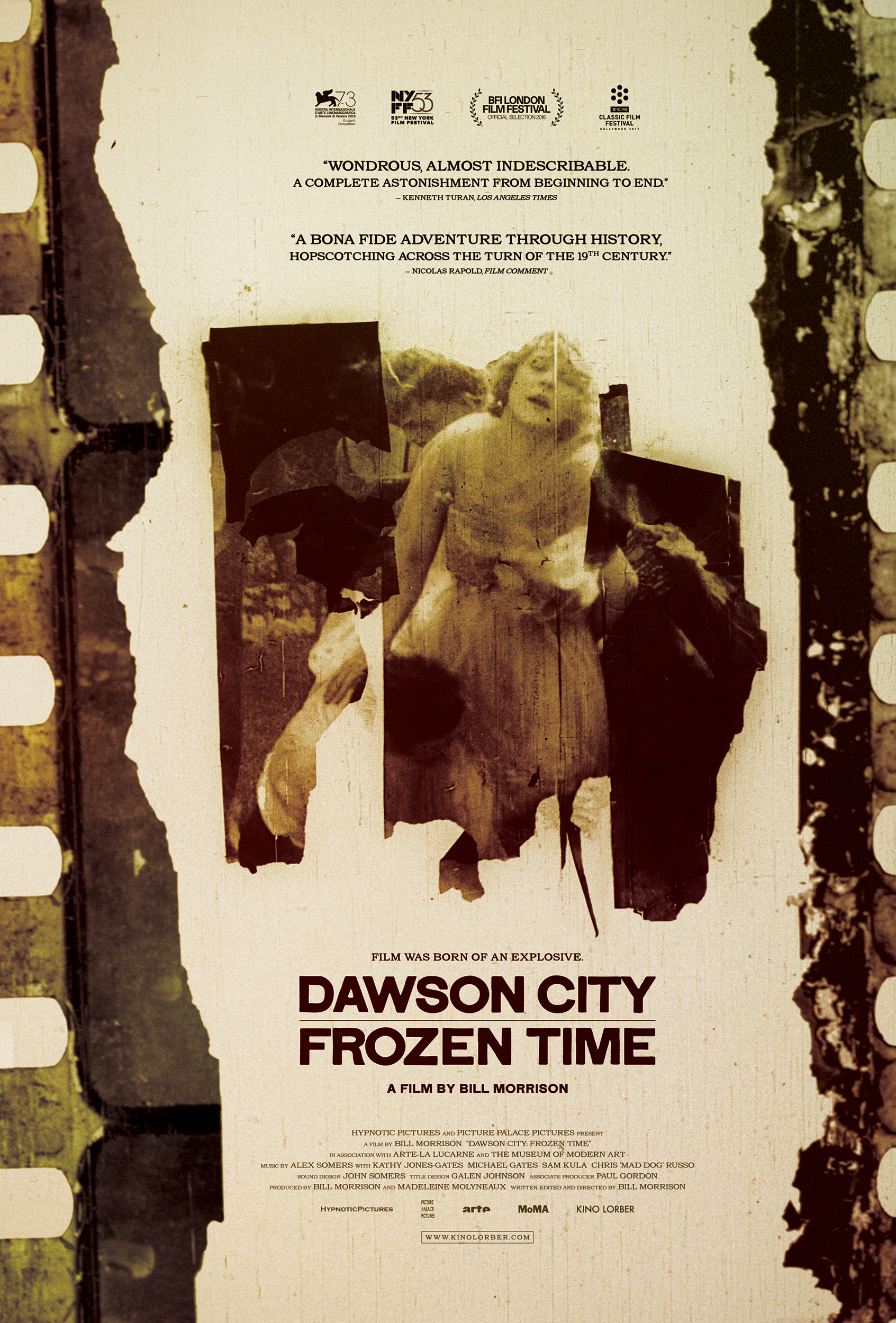

DAWSON CITY: FROZEN TIME

Even now, many people do not care about silent films. Part of it is our disposable society, always rushing to whatever is new, now, next. Part of it is simple lack of foresight: history is not appreciated in the present. Part of it is simple and pure disinterest. Dawson City: Frozen Time does not strictly make the case for film preservation. Instead, it excellently blends the history of this Klondike Gold Rush town to how films that would have been lost forever ended up being saved and preserved, not because anyone there thought they had any value artistic, historic, or financial, but because through a series of random events and accident of geography, it just turned out that way.

With only an opening and closing segment that has on-camera interviews, Dawson City: Frozen Time reveals, in a roundabout way, how these films came to be where they ended up in. The area that now is Dawson City was once the domain of the Han First Nation in Canada until gold was discovered. That sent a flood of people to the area, not just to the future Dawson City but also to the nearby Whitehorse, where a certain Fred Trump opened the Arctic Hotel and Restaurant (read, a brothel), the beginnings of the Trump family fortune.

There, living in the area, was a young newsboy named Sid Grauman. Also stopping by was a dancer named 'Klondike Kate' Rockwell and her partner, Sam Pantages. A conductor who worked in the area was a William Desmond Taylor. In a series of fortuitous events, after they all left, these same figures would play a role in film history: Grauman and Pantages as theater impresarios, opening such famous movie palaces as Grauman's Chinese Theater and the Pantages Theater, host of the Academy Awards, and Taylor became a well-respected film director until his notorious and never-solved murder.

As Dawson City grew, so did the desire to have entertainment, at least eventually of the legal, wholesome kind. Denizens opened the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association (D.A.A.A.), a general community center with a swimming pool that was filled in for hockey (it is Canada, after all).

There was also a place where films could be shown, though many of these films arrived years after their debuts. For example, The Female of the Species, released in 1916, screened in Dawson City on December 23, 1919. Another film, The Price, was released in 1915 but didn't show in Dawson City until January 8, 1920.

The question now arrived as to what to do with all these films. Dawson City was at the tail end of distribution, so once they arrived there, there was nowhere else to send them. A clerk for the bank which acted as agents for the studios, asked if they wanted them returned. The companies all said no, and ordered him to destroy the films. Rather than do that, he had them stored at the old abandoned public library building.

Once sound came along, those who owned the theaters dumped the silents into the Yukon River, or burned them. As for those in the abandoned library, it was decided they would make perfect material to fill in the pool for a new hockey rink.

The years went by, and while every so often a reel would pop out, delighting children by its ability to instantaneously burst into flames, all these films were forgotten until 1978, when the remnants of the D.A.A.A. building was being cleared. There, dozens and dozens of old film cans were rediscovered, having been preserved due to the permafrost in the area.

Dawson City: Frozen Time mixes images from the myriad of formerly lost footage (533 reels) to match the history of the city. The editing is incredibly clever and befitting of the narrative. For example, when the film goes into the gambling of this barely-civilized community, clips from The Price and The Half-Breed pop up (with the clips always showing 'Dawson City Film Find' underneath the title). When it goes into how the community would gather to see the films, we see clips from such formerly lost films as His Madonna (1912).

The condition of the lost footage ranges from the remarkably well-preserved (such as 1919's The Silver Girl) to those which have suffered the ravages of time (What is the Use of Repining from 1913). If you consider that a flaw, you would be wrong: the worn and battered footage lends Dawson City: Frozen Time a certain elegance, even poetic nature to these almost lost films.

Some scenes are still absolutely astonishing in their beauty. Clips from two other Dawson City Film Finds: 1912's The Frogs and 1911's Birth of Flowers are beautiful, almost true artwork brought to life. These clips and the way writer/director/editor Bill Morrison blended them draws you in to this fascinating world and subject (even if perhaps some viewers might tire of reading the film).

What makes Dawson City: Frozen Time more remarkable is not just that movies were accidentally saved for posterity. It was that it was a chronicle of not just this story, but of this community, far from most civilization, where these films and the newsreels were the only glimpses to that far-off outside world. There were many newsreels among the film stock in Dawson City, and among those moments captured were scenes from the 1919 World Series, infamously connected to the Black Sox Scandal. We get glimpses of what life was like for our ancestors, the things that interested and fascinated them, glimpses we might have never had had it not been through a series of fortunate events. Footage from the circa 1907 newsreel A Trip Through Palestine, slightly battered, is still extraordinary in its images of a now-lost world.

It does, however, make one sad to think of all the other films that were not valued at the time and dumped into the Yukon River? Could Theda Bara's Cleopatra have been among those lost to tide? Morrison also works in a collection of photographs, also almost lost to history if not for a few who saw their value and saved them before the glass plates were to be used for a garden's glasshouse.

In a case of how one thing leads to another, those glass plates were used in an Academy Award-nominated documentary about Dawson City, City of Gold in 1957. The film's use of archival footage, pan and zoom of the photographic negatives, and narration inspired future filmmaker Ken Burns to use the same techniques. Coming full circle, the Dawson City footage and the film techniques from City of Gold would find their way into Burns' epic miniseries documentary, Baseball.

Dawson City: Frozen Time relies primarily on on-screen text to reveal the information, and I think that might dull some viewers. For those who love history, film, and a happy ending, Dawson City: Frozen Time captures this stranger-than-truth story, gripping you with history and beautiful images, even in their imperfections.

DECISION: B+

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.