Disraeli has the distinction of being the first biopic to win its lead actor the Best Actor Academy Award. Mr. George Arliss (as he is billed) was highly, highly respected among his peers (no less than Bette Davis credited him for giving Davis her big break in films when no one else wanted her). Arliss, however, is forgotten now; if remembered at all it's for winning the Oscar (and setting the precedent that has won other actors that so-longed-for prize: in the past ten years, SEVEN Best Actor Oscars have gone to someone playing a real-life figure). Disraeli itself has similarly been forgotten (whether British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield himself has been forgotten is up to the reader). I am not going to mount a defense of Disraeli as a great film (its origins as a play very evident in the film). I will say that if one can get past a certain creakiness to it, Disraeli can be a good film.

And on a personal note, a film that desperately cries out for a remake. Why Hollywood doesn't consider remaking something like Disraeli (which has potential and which might appear new to audiences today) but opts to remake actual well-known classics like Ghostbusters, The Magnificent Seven, or Ben-Hur (and that's just this year alone) is a puzzle. I figure it's because Hollywood, averse to risk, wants to cash-in on a recognizable title, but they don't seem to understand that no matter how good the remake is, it will always be compared to the original. Worse, when it goes horribly wrong (as in Ben-Hur), it only makes everyone look flat-out stupid or ridiculous.

Yet here lies Disraeli, a film that, if we are technical, was itself a remake (a now-lost silent version made in 1921); this story has political machinations, romance, espionage, and in the right hands, maybe even a little sex. Disraeli could be remade with some reworking of the material, giving us more of the espionage and intrigue that lies in the story, a mix of House of Cards and The Bourne Supremacy, and be accepted in a way a Ghostbusters wouldn't have to struggle against.

Yet I digress.

Conservative British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (Arliss) faces stiff opposition in Parliament from his archrival, William Gladstone, over foreign policy. Outside Parliament, Disraeli faces opposition from many Britons because of his Jewish heritage (though he himself was Anglican, Disraeli holds his heritage with pride rather than shame). It is in 1874 at his country retreat, where he is enjoying some peace with his wife, Lady Beaconsfield (Florence Arliss, George's real-life wife) that great news has come to him. The Khedive of Egypt, in desperate need of funds, is offering his shares in the Suez Canal. Disraeli knows that ownership of these shares will essentially lead to Britain owning the Canal, providing a vital link to the British Empire, particularly that 'great jewel' in the Crown: India.

Only one or two problems. First, the Bank of England refuses to give Disraeli the funds needed for the purchase. Two, there is evil afoot at the Disraeli country house. One of the guests, Mrs. Travers (Doris Lloyd), a well-placed member of London society, is a spy for the Russians, and they too want the Canal.

To circumvent the first part, Disraeli goes to the only person available to lend the funds to him quickly: Jewish banker Hugh Myers (Ivan F. Simpson). To circumvent the second, that requires Disraeli to play, of all things, matchmaker.

One of his guests is the beautiful society belle Lady Clarissa (Joan Bennett). She is being courted by Viscount Charles (Anthony Bushell), but with no results. Lady Clarissa is firmly in the Disraeli camp, while the Viscount has little interest in state affairs. Disraeli decides to help the young lovers by asking Charles to come work with him (pleasing Lady Clarissa and giving Disraeli someone who could help him in his own imperial ambitions).

Charles makes for a poor spy, inadvertently revealing information to Disraeli's enemies through his body language rather than direct words. Despite Charles' ineptness, Disraeli still hopes to make use of him by sending him, at Clarissa's urging, to Cairo to get at the deal. The Viscount manages to get to the Khedive before Mrs. Travers' agents, and His Majesty accepts Myers' check.

However, the Russians will mount a last effort to get at the Canal. Myers rushes to Disraeli to tell him that he is suddenly bankrupt, the result of nefarious agents. Myers' check will not be honored when the Khedive will try to cash it, but Disraeli has one more card to play. He tricks Mrs. Travers to reveal her part in Myers' financial ruin, then in front of her, forces the Bank of England manager to give Myers an unlimited credit or see the Bank's charter revoked. With that, Myers' finances are restored and the Canal is in British hands.

Disraeli then sheepishly confesses to his wife that he was bluffing (he wouldn't have had the votes to revoke the Bank of England's charter), but the threat worked. With that, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli is able to not just secure the Canal for the British Empire but make his beloved Queen Victoria the new Empress of India.

Disraeli suffers from the flaw that many early talkies had: a deliberate staged and stilted manner. Some credit should go to director Alfred E. Green in that he shot a few scenes in the outdoors (the Disraeli gardens where part of the Charles/Clarissa romance goes on). However, the limitations of the era's technology had him either afraid of editing or moving the camera. Many shots are locked in, with no movement save for the actors.

More than once do the sets look like stages, and Disraeli comes across as a filmed play.

We even get some title cards, indicative of perhaps the film being distributed to silent film houses that didn't have the technology and we sadly have another aspect of early talking films: a more theatrical form of acting.

The courting of Viscount Charles and Lady Clarissa is a bit stiff, but here I am going to give a little leeway in that Charles was a bit stiff as a character (particularly when failing to be romantic). However, there are some wonderful moments when we see that behind the shrewd and calculating mind of the wily Prime Minister there is a tender, soft side, particularly when Lord and Lady Beaconsfield interact. The marriage of Mary and her beloved "Dizzy" looked like a happy one, and the scenes between Mr. and Mrs. Arliss are a delight.

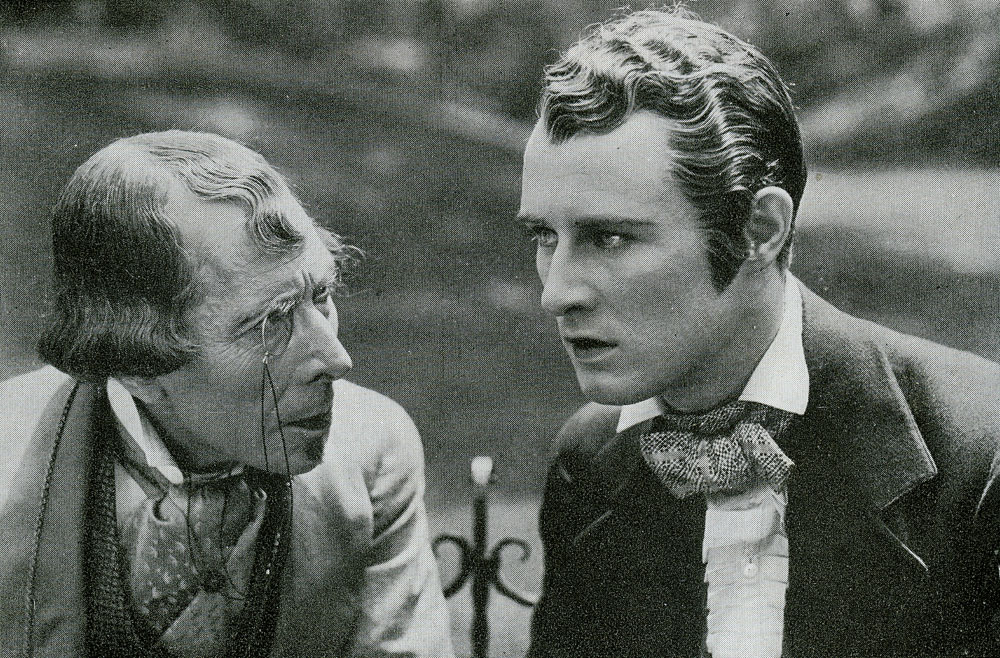

The acting is a bit theatrical, sometimes with a very stiff delivery, but I found Arliss did a pretty good job as Disraeli. He was calculating when dealing with the Bank of England or Mrs. Travers, but also surprisingly light and grandfatherly when he finds himself working to bring Clarissa and Charles together, or when comforting a tearful Clarissa over Charles.

One thing that is surprising about Disraeli is how witty the script is. At one point the Bank of England manager refuses to give the money for what he refers to as "an Egyptian ditch". At another, Clarissa tells Disraeli that she has snubbed Viscount Charles. "How did you snub him?", he asks, to which she replies, "I merely stood up and looked at him".

One of my favorite moments is when Disraeli realizes that Charles has inadvertently revealed the Prime Minister's hands without actually saying anything. He throws his hands in the air and cries out, "What more could have told him for an hour?"

"Do you accuse me of speaking?" the Viscount says in horror.

"No. I accuse you of holding your tongue too outwardly," Disraeli replies.

If you venture into Disraeli, it is only fair to point out that the film is very stagey. Some of the acting is theatrical and/or stiff, there is little in terms of movement (camera or people). However, if you go into it knowing all this, understanding and forgiving the flaws of early sound films, you'll find that Disraeli can be entertaining, even witty.

I firmly believe that if someone remade Disraeli, expanding both the Charles & Clarissa love story and the "Our Man in Cairo" story (telling us how Charles managed to outwit and outrun the Russians pursuing him and the Suez Canal), we might have a much better remake than the horrors we've seen this year (and those coming down the pike: Splash with Channing Tatum as the merman, future plans to remake The Birds). It shows its age, but Disraeli is better than most films of the Transitional Era.

|

| 1804-1881 |

DECISION: B-

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.