Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Ziegfeld Follies: A Review

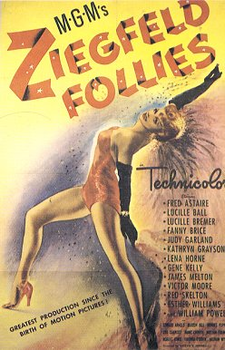

ZIEGFELD FOLLIES

Florence Ziegfeld was the impresario of the grand, extravagant, and always entertaining Follies on Broadway. They had lavish costumes, elaborate sets, some comedy, some music, and girls, girls, girls. Hundreds of beautiful girls. If anything, the Ziegfeld Follies were always a glorification of the American Girl. MGM took this idea and decided they were going to do their own version of a Ziegfeld Follies by making a movie called Ziegfeld Follies. The end result, while perhaps a bit dated now, has some really fascinating moments and numbers that would have made Ziggy proud.

Death can't keep a good showman down, as Ziegfeld Follies shows. Even though Broadway impresario Florence Ziegfeld (William Powell, in a cameo recreating his role from The Great Ziegfeld), had been dead for some time, he still dreams of what he could do if given one more chance to mount one of his Follies. We get a short remembrance of what his Follies used to look like back in 1907 (courtesy of a remarkably brilliant stop-motion animation sequence courtesy of Bunin's Puppets). His Follies has big stars like Will Rogers, Fanny Brice, and Eddie Cantor (the last done up in Cantor's traditional blackface, historically accurate and non-controversial at the time but one of our two racially insensitive moments). Now, Ziegfeld dreams of what his new Follies would look like. He imagines it would start with his good friend Fred Astaire introducing a bevy of beauties...

From there, Ziegfeld Follies segways into a series of numbers, some musical, some comedy, with nothing to connect them one to the other. We get numbers that appeal to high culture (a number from the opera La Traviata) to more vaudeville/working-class shtick (Fanny Brice, the only actual Ziegfeld Follies star to be in Ziegfeld Follies in a routine about a winning lottery ticket that her husband gave away in lieu of rent).

Fred Astaire has four musical numbers (the opening number Here's to the Girls, the posh This Heart of Mine, the balletic Limehouse Blues and one more number, both of which I will discuss later). Esther Williams has a short number where we see her perform a water ballet. Lena Horne has a musical number where she sings Love. Judy Garland spoofs a press interview where a grand dame of film expresses a mad desire to get away from lofty biopics to 'acting with her torso' and doing a song-and-dance in A Great Lady Has "An Interview".

The musical number The Babbitt and the Bromide, the final Astaire number, has him doing a dance routine with Gene Kelly, the only male film dancer to rival Astaire and the only time they worked together on film (not counting a joint appearance in That's Entertainment II, a collection of classic Hollywood musical clips). The film closes in an elaborate number involving bubbles with Kathryn Grayson singing Beauty.

The various comedy numbers are Number Please, where Keenan Wynne attempts to make a telephone call and gets nothing but frustration for his efforts, Pay the Two Dollars, where poor schnook Victor Moore gets into further and further trouble due his lawyer Edward Arnold's refusal to 'pay two dollars' for a minor fine, the aforementioned A Sweepstakes Ticket, where Brice and husband (Hume Cronyn) attempt to get a winning Irish Sweepstakes lottery ticket from their landlord (William Frawley), and When Television Comes, a recreation of a radio skit by Red Skelton.

All these various elements are put together to make up Ziegfeld Follies.

I mentioned that I would discuss both Limehouse Blues and the last Astaire number (The Babbitt and the Bromide). I also mentioned that there were two racially insensitive moments in Ziegfeld Follies. Let's tackle the second part first. Limehouse Blues is perhaps the most elaborately artistic dance number in the film, quite balletic and artistically ambitious. It's one of Fred Astaire's grandest musical numbers.

It also has him and his dance partner, Lucille Bremer, in essentially yellowface, with both of them wearing make up to give them more 'Asian-looking' eyes. That alone and in of itself is already ghastly. Hearing lyrics like the Limehouse district in London is 'where Orientals love to play' makes things worse.

Granted, we have to remember that in 1946 when Ziegfeld Follies finally premiered after a protracted production, seeing people in blackface (as we do in the animated Follies recreation) or seeing "Asian" performances was not considered offensive (at least to non-African-Americans or non-Asians). We should also remember that Eddie Cantor (or his animated figure) was known for doing song-and-dance routines in blackface by contemporary audiences. Finally, we also should note that neither Cantor or Astaire themselves ever had any bigotry attached to them.

It's just a product of the times, and while it doesn't justify such acts or make them pretty shocking to today's audience, things like these should be taken in context, understood to be acceptable at the time but not now. The Limehouse Blues number itself is quite beautiful, and the opening animation stands the test of time. However, they both should be seen with a jaundiced eye, aware of the flaws but also acknowledging the craftsmanship behind them.

Now on to The Babbitt and the Bromide number. I don't claim to have expertise on the dance styling of Fred Astaire vs. Gene Kelly, but seeing them together in this one-time appearance we can see that they were different but brilliant in their own way. Astaire, taller and leaner, with longer limbs, is smoother, more graceful and elegant. Kelly, shorter, more muscular with a boxier, square shape, is sharper in his movements, more direct and blunt, almost attacking. We can see the fabled differences between them: why Astaire was better known for a posh manner and Kelly seen as more 'working class'.

It's wonderful seeing them together, their interplay between them a teaming of equals. Just for that alone Ziegfeld Follies is something special.

Also brilliant is Garland spoofing the pretensions of artists as well as the media frenzy. A Great Lady Has "An Interview" was originally conceived for Greer Garson (who was best known for biopics and heavy dramatic roles), but she turned it down. Garland was brought in and runs away with the number as she sings and dances while detailing her newest picture: a biopic of the inventor of the safety pin. It's a great number, both mocking and self-mocking, that lends lightness to the proceedings.

In terms of other aspects, a few of them are hit and miss. Since Ziegfeld Follies is billed alphabetically, Lucille Ball gets second billing, but while she proves that she was quite striking-looking, she had no dialogue, her scene consisting of being a tamer to a group of women in catsuits and cracking the whip every so often. It comes across as slightly hilarious.

The Esther Williams number is a poor example of what made Williams various water films so interesting to watch. This appears to be included merely for the fact that Williams was a big star at the time, and even in a film that has no plot, the Williams number appears superfluous.

The comedy numbers are the ones that would be dated to contemporary audiences. Figures like Wynn, Brice, and Skelton were much better known in 1946 than today (with the possible exception of Brice, who is better known thanks to her biopic Funny Girl). As such, modern audiences might wonder whether they should be skipped. I would recommend that you not pass them.

The surprise is the Number Please routine with Keenan Wynn (and as a side note, Ben Foster would be great to cast as Wynn, allowing Foster to do something comic). Wynn's slowly building frustration at his inability to get through on a phone call is amusing. Skelton manages to use his face and voice in a hilarious way as he inadvertently grows drunker reminiscent, curiously enough, of what Ball did in her famous Vitameatavegamin routine from I Love Lucy. Skelton's recitation of a Garter Poem is slightly naughty but funny.

Brice works her Yiddish charms as the lower-class hausfrau who tries to seduce her equally-schlubby landlord. Cronyn is the surprise as her equally inept husband. The Give Him Two Dollars routine, stylized for the film, is also hilarious in its buildup of Moore's frustrations at being snookered by his eager but stubbornly stupid attorney.

It's a rare moment to see three great comedians doing great work, and it's just a terrible shame that they aren't as well-remembered as they should be. We have Ziegfeld Follies to give us a glimpse as to why each of them were highly recognized and popular at the time.

Ziegfeld Follies is a bit of a time capsule into both what an actual Ziegfeld Follies would have looked like and what kind of personalities and styles were popular in the immediate post-war era. It is a bit dated in certain aspects, but on the whole a fascinating film that has no purpose other than to entertain. It does so, with a few missteps, but done well enough to make it a lavish spectacle with humor.

DECISION: B+

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.