This review is part of the Summer Under the Stars Blogathon. Today's star is Tom Courtenay.

There was a time in British cinema where "the angry young man" dominated. These tales of working-class alienation and despair were prominent with such films as Look Back in Anger and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Even Sir Laurence Olivier got into the act with The Entertainer. Another film entry into the kitchen sink drama is The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner. This is an absolutely brilliant film, with a standout performance by Tom Courtenay as our antihero.

Young Colin Smith (Courtenay) has been sent to Ruxton Towers, a youth detention center (what is called a borstal in Britain) after having been found guilty of breaking into a bakery and stealing money. Here, Smith is at most indifferent to things, at most hostile to the people around him. He has one standout quality: Colin is an excellent athlete.

This piques the attention of the borstal Governor (Michael Redgrave). Ruxton Towers will have the chance to compete in an athletic tournament with the posh Ranley School. The Governor is sure that Smith will defeat Ranley in long-distance running. Smith does have great skill in this event and soon gets the priviledge of running through the nearby fields unaccompanied. As he runs, Colin has the chance to reflect on his life prior to Ruxton Towers.

He remembers his father's death and how his mother (Avis Bunnage) spends his father's life insurance money on needless luxuries such as a television and a fur coat. He also sees Mrs. Smith bring in Gordon (Charles Dyer), her new lover to live at the home with Colin and his younger siblings. He remembers his best mate Mike (James Bolam) and the scrapes that they got into together. He remembers Audrey (Topsy Jane), his first love and first lover. He also thinks about what the future holds for Colin Smith. He remembers the break-in and his efforts to pull a fast one on the cop doggedly pursuing him. He remembers how he was eventually caught, thanks to the rain.

Now he is here at Ruxton Towers, running but going nowhere. The Governor dreams of glory for Ruxton and by extension for himself. On race day itself, Colin soon overtakes Ranley's best runner, the upper-class Gunthorpe (James Fox). As he nears the finish line, the past comes at Colin in flashes. His mother. His father. The cop. Mike. Audrey. Gordon. Will Colin win the race, or will he win for himself?

I think The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner has one of the greatest performances in film in Tom Courtenay. Colin Smith is another angry young man, frustrated in life but finding no escape. I'm reminded of a line from Pet Shop Boys' West End Girls: "we've got no future; we've got no past". That describes Colin Smith perfectly. He sees what the future holds for him: a life like his father's. This is not what he wants. I think that he wants near-endless visits to Skegness with Audrey like the one that he took with her, Mike and Audrey's BFF Gladys (Julia Foster) who is also Mike's girlfriend.

However, that would take money, which Colin does not have. Worse, he sees how his mother flittered it away. He is powerless to persuade her not to splurge so rampantly. He is powerless to stop Gordon from trying to usurp Colin's place as head of the family. In short, he is powerless.

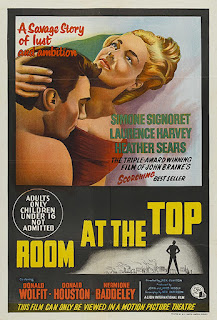

Unlike other angry young men in the kitchen sink genre, Colin Smith is a remarkably decent, thoughtful young man. He is angry, but it is the world around him that has shaped him so. Another angry young man, Laurence Harvey in Room at the Top, carried a permanent chip on his shoulder. Colin, on the other hand, shows a thoughtful, tender side, in particular with Audrey. He is a reflective young man, aware of the hardness of life and his inability to change it despite his wish to. "All I know is that you've got to run, running without knowing why, through fields and woods. And the winning post is no end, even though the balmy crowd might be cheering themselves daft". Colin understands through his time at Ruxton Towers that, for all the success that he might have for his athletic skills, he is still very much alone, condemned to stay in one place.

Metaphor has never been so well used in film as it is for The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner.

Yet, I have wandered off from Tom Courtenay's performance. His Colin Smith is an antihero for the ages. Colin is cynical and sullen. Yet within him, Colin is also tender and caring. He has a brief scene where he looks in on his dying father. As everyone else seems to have forgotten the cantankerous old man, Colin quietly covers him with his blanket. Courtenay reveals Colin's anger at his mother's frivolousness to downright disinterest in her late husband on the family shopping spree. Sitting quietly, smoking, he observes her buying needless thing after needless thing, his impotency and condemnation clear.

Courtenay reveals Colin's tender side when he is with Jane's Audrey. "I know enough, you know, to want to know more," he tells her. This line from Allan Sillitoe's adaptation of his own short story reveals so much about Colin. He thirsts for something more, something better, but knows that he will not find it. I think that he is disgusted with the world as it is but cannot find a way to change it.

As his benevolent antagonist, Michael Redgrave is correct as the pompous Governor. He imagines that he cares about the young men at Ruxton Towers and in Colin's future. In reality, Colin and the audience knows that the Governor cares about glory and tribute for the institution and by extension, for himself. In the climatic race conclusion, Colin's smile is countered by the Governor's scowl. In this exchange, brilliantly directed by Tony Richardson, we see not just their battle coming to its conclusion. We see in a sense that battle between the haves and the have-nots.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner reveals itself in other ways. The use of the traditional British hymn Jerusalem is used ironically. This ode to patriotism is heard twice: in the opening and in counter for when an escaped borstal resident is returned and punished. The second use of Jerusalem is also when a "concert" for the boys is ended. This concert consists of a man doing bird imitations and an elderly couple singing a very old song in an old-fashioned way. It is such a laughable sight to have a bird imitator attempt to entertain young men. It does, however, reveal that disconnect between those in power and those under them. It is a credit to both Richardson and Courtenay that one is unsure if Colin Smith is singing along to Jerusalem because he genuinely believes in its sentiment or to mock said sentiment.

In one of the flashbacks, Mike and Colin have muted a television speech extolling a revived patriotism in the new Elizabethan age. The delight Mike and Colin have at how silly the man looks reveals much about their world and views on it.

Richardson even manages to have a bit of comedy in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner. The break-in ends with deliberately sped-up action that would be seen in a silent movie, down to John Addison's music. Colin's efforts to hide the discovered money are also amusing. It does show that even a kitchen sink drama can have a genuine sense of fun.

I finished The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner highly impressed with everything in it. Colin Smith is an antihero that you end up admiring. He is unbowed and true to himself. "I got caught. Didn't run fast enough," he tells an interviewer at Ruxton Towers. There is a lot of meaning in that line. The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner is simply brilliant, with a standout performance by Tom Courtenay. Anyone who takes time to see The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner will find a masterclass of storytelling.