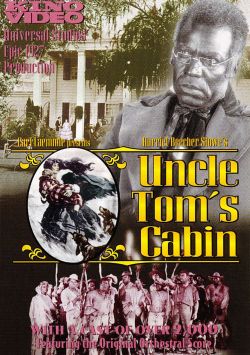

UNCLE TOM'S CABIN

Our second African-American film involves one of the shameful chapters in American history and one that still haunts America: the peculiar institution of slavery.

Uncle Tom's Cabin is a book people know but rarely read. The term 'Uncle Tom' has become a pejorative one, suggesting subservience and a willingness to play idiot, to scrape before others, to please someone the 'uncle tom' perceive to be 'superior'. In short, it's akin to being a 'traitor'. The truth, as always, is far more complex than popular ideas. The whole issue around Uncle Tom's Cabin, book and film, is so tinged with animosity and racial animus that one can't enter it without some trepidation. It is truly a case of not seeing the forest for the trees. The silent film version of Uncle Tom's Cabin may not square with the book (though again, not having read it I'm in no position at the moment to pass judgment on it). However, I found myself moved emotionally by it, and while the liberties the film takes with both the story and portrayal of slavery may be surprising, there is still a great deal of good within Uncle Tom's Cabin.

We start in 1856, where fair-skinned slave Eliza (Margarita Fischer) is about to marry George Harris (Arthur Edmund Carew), another fair-skinned slave from a neighboring plantation. In an uncharacteristic move in the South, Eliza's masters, the Shelbys, give her a big wedding. Everyone is invited, and the slaves, particularly dear old Uncle Tom (James B. Lowe) is happy for Eliza and George. All except George's master, who is enraged that his engineer is marrying without permission. The Shelbys offer to buy George, but his master refuses, ordering him to return.

Somehow, George and Eliza have a child, Harry (Lassie Lou Ahern), who not surprisingly is basically white. Mr. Shelby has fallen on hard times financially, and his creditor demands the sale of Eliza and Uncle Tom. Mr. Shelby has no recourse but to sell some of his slaves, but he will not sell Eliza. Seeing Harry, the creditor asks for the tyke instead. Eliza learns of this, and she will not leave her child to such a fate. With that, she flees, making a harrowing journey in winter across the frozen Ohio River, with dogs and slave-catchers hot on her trail. While she finds shelter with a Quaker family in the free state, the Dredd Scott decision compels both her and Harry to be returned.

Thus showing that the Supreme Court is not always right...just a thought.

Uncle Tom too is sold, and being a man of strong faith, he trusts God will not just bring him through but protect the wife and child he is forcibly separated from. Sold down the river (which, by the way, a slavery term from which the expression comes from), Uncle Tom comes across Little Eva (Virginia Gray), one of the saintliest figures to ever come across 19th Century melodrama, let alone silent cinema. She persuades her father to buy Uncle Tom. However, unbeknown to everyone, George, passing for white, works on the same riverboat, and both Eliza and Harry are aboard as well. George has been searching for his wife and child, and the slave catchers decide they can make more money by selling Harry. In a particularly brutal scene, Harry is separated from his mother, with Eliza desperate to hold on to him.

She and Tom are sold off, but fortune does bring them together eventually. Little Eva is a saint, and even Topsy (Mona Ray), a thieving little black girl, is awash in tears after Little Eva dies. As I said, Tom and Eliza are brought together after Emancipation, which delights Tom. Tom's final owner is a cruel man, but in the ways of good old 19th Century melodrama the woman who is being replaced in affection by Eliza by their new owner turns out to be Eliza's long-lost mother! The Union troops come in just in time to save Eliza and her mother, with Tom having been murdered by the slaveholder. As it so happens, George has spotted Harry earlier, rescued him and simultaneously been freed by the Union Army enforcing the Proclamation. The troops come in to save the women, and the entire family is reunited.

There are things to look at in Uncle Tom's Cabin with some misgivings. One is the blackface aspect. Ray's Topsy is really a very uncomfortable thing to watch, as she descends into stereotypes and blatant idiocy. Similarly, Gray's Little Eva is less endearing and more irritating. She comes across as equally idiotic in her saintliness, as a little girl so sickeningly-sweet that you really don't mind if she dies. Having a halo appear around Little Eva as she gently teaches the wicked little Topsy that stealing and lying is wrong puts an extra bit of heavy-handedness on the entire scene.

Adding to that Ray's wild overacting (even for a silent film), particularly in Little Eva's death scene.

We can quibble about having non-white actors playing slaves, but here I'm willing to cut the film a little bit of slack. After all, it's still a bit hard to show interracial couples on screen large or small. Granted, the times they are a'changin', but things haven't gotten very far. Therefore, it made some sense to cast white actors, explaining that they were fair-skinned blacks rather than suggest miscegenation. In 1927 this would have been a scandal. One has to look at it that way, rather than say 'oh, how silly'.

Less pleasing and more outlandish is the title card that says "Gentle rule of the slaves was typical of the South". It's a silly idea and pretty insulting to our intelligence. A quick scene of black children chasing after watermelons also is highly uncomfortable. I also question Eliza's slave cabin, which is rather pimped out and cushy for a slave's digs, even one as favored and white as Eliza.

Having said all that, and with some questions of how slavery was portrayed, Uncle Tom's Cabin also has some simply heartbreaking, even thrilling moments. Eliza's flight across the Ohio is shockingly exciting and intense. It is reminiscent of a scene in D.W. Griffith's Way Down East when someone crosses a frozen river. However, Fischer's performance as she is desperate to escape to save her child is a powerful moment. While perhaps director Harry A. Pollard didn't have this in mind, seeing the forced separation of families, sadly a true fact of that 'peculiar institution', is thought-provoking. Seeing Tom separated from his wife and children is extremely upsetting, both when they learn of it and when it actually happens. Similarly, the forced taking of Harry from a desperate Eliza I think will tear at people's hearts.

Perhaps because Harry and Eliza are 'white', white audiences could identify with the situation and the true horror of it. Pollard really does well as Eliza makes a desperate race to save Harry, and people not moved by this will be extremely hard. We also see great camera work as the camera moves from George, who can only watch helplessly as his wife and child are lost to him a second time.

Like in any good silent film, foreshadowing works well for it. A storm cloud gathers over the Capital just before the Civil War breaks out, and it's a subtle nod to what is about to descend on America that we as an audience get.

In terms of performances I think Lowe, the only African-American in the cast, did not make Uncle Tom anyone's fool and was far from the stereotype of the grinning idiot who scrapes to please his 'massa'. Tom is a man of faith, but he is also joyful at reading about the Emancipation Proclamation. This belies the concept that Uncle Tom wants to be a slave, that he is eternally loyal to his master. No 'uncle Tom' would want freedom, but this Uncle Tom certainly did. This Uncle Tom also stood up for himself and fought the slaveowner. That he forgave him and his two black henchmen (whom I would say were more caricatures than that of Uncle Tom) is less to do with idiocy than in the character's deep Christian faith and him attempting to 'forgive as he has been forgiven'.

Looking across a good almost 100 years since the film's debut, and more than a hundred years since the book's publication, it is fascinating to see how the myth of "Uncle Tom", a traitor to his race, a being who betrays his people's and his own interest at the cost of their/his freedom, may be more fiction than fact. Until one reads the book it is impossible to say for certain whether Uncle Tom's Cabin is accurate to the source material. It is even harder to say whether Uncle Tom was really an "Uncle Tom". This version of the story, while not without some terrible flaws, is a well-made film, with some truly moving moments and excellent camera work.

It may not be completely historically or literarily accurate, but is a strong film.

|

| I like this Little Eva better... |

DECISION: A-

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.