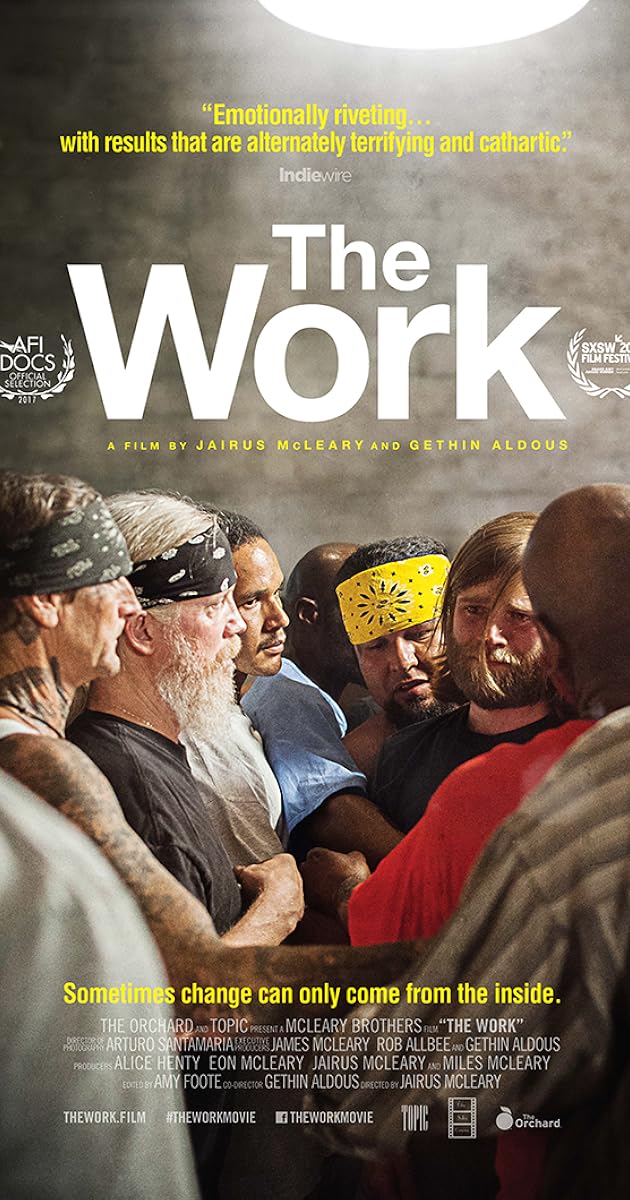

THE WORK

The Work is an extraordinary film, forcing the viewer to question their ideas of who and what criminals are, what masculinity is, and the ideas of rehabilitation versus incarceration. It does not shy away from the unsavory aspects of crime and punishment, as well as vulnerable men, something that even now is seen as an oxymoron. Co-directed by Jairus McLeary and Gethin Aldous, The Work holds you, makes no statements about what the viewer should think about what the viewer sees, but it gives one pause to ask themselves questions about how they would react and be in similar circumstances.

The Inside Circle Foundation conducts group therapy sessions for convicted men. Twice a year the public is invited to join a four-day intensive group therapy session at Folsom State Prison (the one made famous by the Johnny Cash song). The Work chronicles one such session, focusing on three men 'on the outside': Charles, a bartender, Chris, a museum associate, and Brian, a teacher's assistant. They go in to the prison where they are grouped with men serving time for various crimes from kidnapping to attempted murder.

The convicts agree to leave any and all gang politics and racial segregation outside the sessions. This affords them a chance to work together in delving into their deepest, most personal issues. Those on the outside also participate, informally joining with two prisoners they choose with whom they will share their feelings, hurts, and pain. This smaller group will in turn join a slightly larger group with facilitators who will guide the convicts and free men to open up about all their emotional issues and scars.

During the four days of therapy, both the convicts and free men open up in unsparing, painful ways about their emotions, raw and uncensored. We see convicts openly weep for their dead sisters and howl in pain about the absence of their fathers (a recurring theme for most if not all the men was either the total absence of their father or the failure of their fathers to be guides in some way). Both the convicts and free men reveal their innermost emotions in terms that prove shocking and surprising.

After the four days of emotional soul-baring, the free men return to society, more aware of who they are, while those on the inside continue to heal. The Work ends by noting that in the 17 years the Inside Circle Foundation has been running their program, over 40 convicts who have participated have been released.

.jpg) Their recidivism rate?

Their recidivism rate? Zero.

The Work will shock those who have preconceived notions about men in general and convicts in specific. The notion that someone like the Native American prisoner Dark Cloud, who openly talks about almost chopping a man in half, sobbing uncontrollably over leaving his mother for his father who was no good for him, leaves one almost in disbelief.

While he wants to be vulnerable (his words), at one point he lunges at Brian when he whispers that Dark Cloud is 'gentle' with only the other men holding him back saving Brian. The inner struggle the convicts have and how they can be so open in a place where emotion is seen as weakness is perhaps startling but also courageous.

Again and we see how for many if not all the men, free and convicted, their fathers are a specter hanging over their lives. Brian, who says that one of his issues is being quick to judge and has issues when it comes to perceived disrespect, shocks the viewer when he admits he wants to kill when he feels disrespected. At a certain point, he too becomes so physical that at least seven of these hardened criminals have to hold him down to stop him from doing violence to others or himself.

And he's one of the ones on the outside.

Not that The Work is all somber and dour. These men can have moments of levity. After Brian is calmed, it's noted that he got a cut on his forehead. Someone mentions that he can now tell people he got that injury in a prison fight at Folsom Prison, causing everyone, even Brian, to burst out into laughter. Those moments, however, are few, for The Work is as intense as the therapy sessions the viewer sees.

The rawness, the emotional impact of the film never wavers.

I think the power of The Work comes from the fact that again, it challenges many ideas. For those who don't know anyone in prison, it is easy to dismiss them as unrepentant, uncaring, unfeeling individuals, even 'non-persons' who are either evil or stupid. The Work forces the viewer to see that despite having been affiliated with the Bloods, the Crypts, the Aryan Nation, or even other racial prison gangs like The Skins (for Native Americans) or The Others (Pacific Islanders), these men are also sons, husbands, and fathers. They are individuals with pasts, with hurts, with their own baggage that is doubled by the fact that some may never leave the prison except in a coffin.

As easy it is to dismiss convicts, some of whom committed shocking crimes, as 'out of sight, out of mind', we see that they are also wounded souls; we see them as individuals like you and me, who through their own actions and the actions of others ended up in a place that should be one of total despair, but where they found hope and perhaps emotional peace.

The Work also makes one question preconceived notions of masculinity. Even in our more open society, men are still expected to be stoic, to not cry, to not show emotion, to keep things within. However, many men, especially fatherless men, have a great wound within them that society does not allow them to show.

The theme of fatherlessness appears over and over again, the specter of absent or disengaged fathers shaping so many of these men. Near the end of The Work, one talks about doing this for 'the fatherless sons', mentioning how he was a fatherless son, his father was a fatherless son, his grandfather was a fatherless son, and his own son is growing up a fatherless son. The cycle impacts all the men on the inside and out, and it is something that gives the viewer pause to think.

Over and over we see men sob and wail uncontrollably, their rage and hurt openly expressed. Even Chris, who said on Day One that he wasn't going to cry or couldn't really relate to the men, ended up in tears when he forced himself to think on his own father.

Chris' father, unlike some of the others like Charles, didn't physically abandon him or failed to provide. He might even have shown more love than some of the other men's fathers. However, Chris has been directional-less for many years, unsure about what to do with his life. Near the end, he tells of how on many occasions as a child he wanted to help his father do something like fix the car. His father would ask Chris for a tool of some kind, but Chris kept bringing the wrong one because he didn't know which one was which. His dad, finally flustered, told him to just go inside with his mother and he would take care of it.

While to some this comment would be innocuous, to Chris it shaped in him the idea of a lack of worth, of rejection, of not being good. The Work shows how the other men metaphorically block him from his 'father', who keeps telling Chris to go back into the house to his mother. It's up to Chris to metaphorically 'break on through to the other side' and reach his father.

The Work hits one emotionally, and what is interesting is that while it does not walk away from the men's actions that brought them there, it does not dwell on them as 'criminals' but as men, wounded men. It might be tempting to dismiss the work of the Inside Circle Foundation as a lot of New Age hippie-drippy nonsense, healing convicts with candles and a good cry.

As a side note, it does bring to mind a short-lived moment where men would go into the woods, beat drums and howl uncontrollably. Most people mocked such behavior, but it does feed into the ideas of 'masculinity' that The Work challenges. The film shows that both those on the inside and outside can have emotional issues that incarceration does not heal, and which in the end does not help if and when they are released into a society that thinks little to nothing of them.

If one dismisses the work done in The Work, it shows that a certain mindset has set in, which is unfortunate. Yes, the notion of one of the founders doing some kind of chant with a response, the lighting of candles, sharing various 'daddy issues' or playing a little Music From the Hearts of Space may look bizarre, even laughable. However, the fact that the Inside Circle Foundation has had a 100% success rate in making the former convicts into members of society shows that perhaps a little group therapy goes a long way.

It would have been nice to have seen some of those who have left prison after they had done 'the work' (maybe a sequel?) and/or seen how Charles, Chris and Brian are doing or how the came to be part of the program. However, those are minor points in an extraordinary film.

I admit I would be terrified to go into Folsom Prison, let alone pick two convicts to share my deepest emotional issues with (and that's considering I worked in a parole/probation violators center). However, The Work, in a gripping and powerful way, brings a much-needed human face to those incarcerated. It is perhaps strange, but also deeply moving, to see these men break down and admit vulnerability.

At a time when prison and criminal justice reform is one of the few issues to find bipartisan support, The Work is an invaluable documentary to show that for too long we have focused on incarceration and not rehabilitation. Prison was meant for both punishment and reflection, and for too long the focus has been on the former at the expense of the latter. The Work demonstrates that we should look at both sides and forces us to see men in prison as something people often don't see them as: human. Those on the inside and outside need encouragement, and The Work may turn minds and hearts just as the program has done for those who participate in it.

DECISION: A-

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.