MR. & MRS. SMITH

This review is part of the Summer Under the Stars Blogathon. Today's star is Carole Lombard.

While Alfred Hitchcock was the Master of Suspense, there is one outlier in his oeuvre that still puzzles people today: the romantic comedy Mr. & Mrs. Smith. Short and breeze, Mr. & Mrs. Smith works well despite its questionable logic.

David Smith (Robert Montgomery) and his wife Ann (Carole Lombard) are a battling but ultimately couple. After their last three-day fight ends, Ann asks a rhetorical question: if he could do it over again, would he marry her?

David goes for the honest route and says No. While he loves her, he would keep his freedom first and for a bit longer. This is an exceptionally dumb answer, but it turns out to be prophetic. The clerk from where they got married comes to New York and tells David that, due to a legal technicality, their marriage is invalid. Unfortunately for David, the clerk is an old family friend of Ann's, and he stops by to see her and tells her the same.

David thinks he'll get a mistress first, then a wife. He did not count on Ann's rage at his attempted seduction. Soon, Ann is living the single girl life while David is relegated to living at his club. She also is wooed by Jefferson "Jeff" Custer (Gene Raymond), a Southern gentleman who is also David's law partner. As David continues his efforts to win his wife back, Ann has growing and conflicting feelings for her potentially former husband. Will our cuckoo lovebirds find each other's love nests?

I figure many would be astonished at the idea that Alfred Hitchcock could make a straightforward screwball comedy. However, Mr. & Mrs. Smith proves that Hitchcock was capable of working in this genre. The movie moves quite quickly to where one is surprised that so much can fit into a breezy 94 minutes.

One can see how well Hitchcock could work within this genre in certain scenes. For example, there is a great moment when both David and Ann end up in a swanky nightclub. A clearly embarrassed David is already aghast at the girls his club friend Chuck (Jack Carson) whipped up for them. His first attempts to fool Ann by miming a conversation with the more attractive female next to him is amusing. That is followed by his disastrous efforts to get out of the club by giving himself a bloody nose.

Not to be outdone, Lombard has a great moment herself when Ann and Jeff go to the World's Fair and are stuck on a ride where they must endure the rain. Seeing the elegant Ann all wet and flustered, followed by her efforts to be coy with a courtly but drunk Jeff show Lombard's skills as a comedienne. She has another great moment when she expresses some puzzlement over why her wedding suit no longer fits three years later. The gag works, and Lombard sells her mix of embarrassment and attempted befuddlement well.

Mr. & Mrs. Smith has not only amusing comic bits but a surprising amount of risqué moments. Early on, Ann is playing a version of footsie with David, pulling away as soon as he says he would not remarry her. David at one point writes, "Miss Krausheimer" when thinking about his unexpected situation with Ann. He then crosses it out and substitutes "Mistress" for "Miss". While "mistress" is technically used correctly, the implications around "mistress" are all but poking at the censors. The film ends with her skis crossing each other, which is as overt a suggestion of sex as the censors would allow (or miss).

Lombard and Montgomery work well together as this oddball couple. Lombard had an exceptional ability to be simultaneously glamourous and silly. Here, she does wonderfully as Ann, who has something of a childlike innocence when it comes to David but who is also understandably angry at his behavior. She has a wonderful moment late in Mr. & Mrs. Smith when she attempts to hoodwink him by pretending to be with Jeff by making a lot of noise and carrying a one-sided conversation with him.

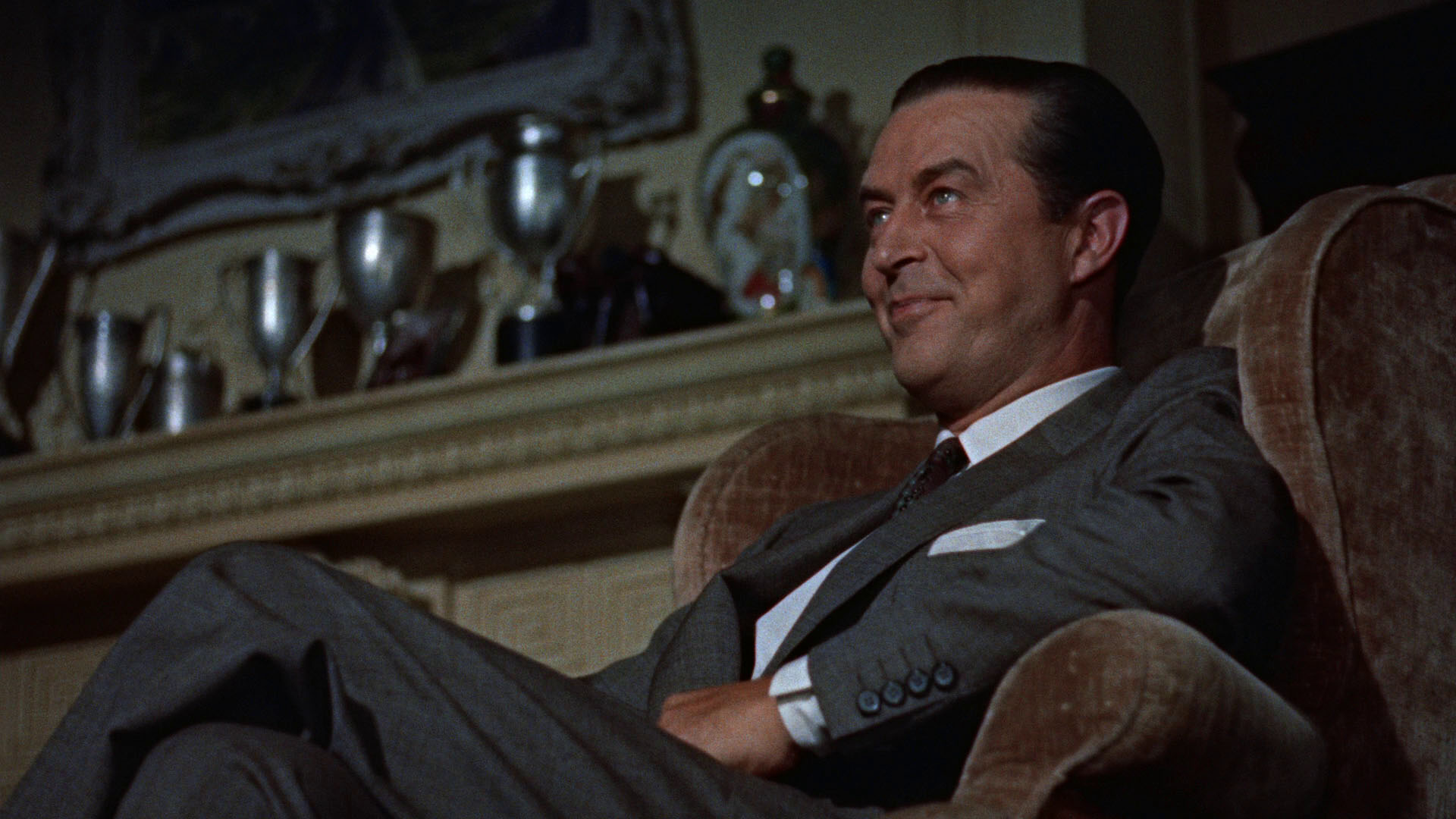

Montgomery too does great work as David. To be fair, it is hard not to see David as a jerk, forever doing or saying idiotic and insensitive things. That we like him at all is a credit to his abilities as an actor. In smaller roles, Gene Raymond and Jack Carson were amusing. Raymond's Jeff had a great moment when playing drunk. The Southern accent was not overdone, and even allowed for some humor at his expense. David, upon learning that Jeff has asked Ann out, calls him a "hillbilly ambulance chaser". Not to be outdone, Jefferson's parents are horrified when learning of the Ann/David situation. "What kind of white trash are your going around with?", Jeff's parents angrily ask.

Carson's more genial and randy Chuckie was equally amusing and almost stole the film in his few scenes. His telephone call to one of his girls, complete with blowing kisses, was light and enjoyable.

Norman Krasna's screenplay flows well, even if the logic of the plot is extremely thin (it's highly dubious that the marriage would be invalid due to a geographical dispute over who could perform the ceremony). Still, a film like Mr. & Mrs. Smith does not exist out of logic. In fact, it is the illogic that makes it more amusing.

Finally, Mr. & Mrs. Smith was the final film released in Carole Lombard's lifetime. Her tragic early death in an airplane crash is still one of the greatest losses to film. One can only imagine how, had she lived, she might have become one of Hitchcock's cool blondes in a more dramatic role.

Alfred Hitchcock had comedy bits in some of his films and at least one other film, The Trouble With Harry, is more comedic albeit of a black variety. As the only pure comedy in his filmography, Mr. & Mrs. Smith more than stands on its own as a nice, pleasant film.

Hitch, we hardly knew you...

.jpg)

_theatrical_poster_(retouched).jpg)