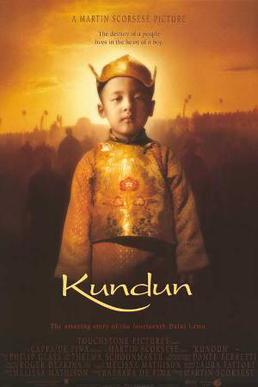

It was a few decades ago when Tibet was the cause du jour for many, particularly in the arts. That is, until the Chinese market became so lucrative that many would willingly ignore the human rights violations and systematic oppression of religion and minorities to get at the yuan. Kundun, a biographical film of the Fourteenth and current Dalai Lama, was the second of two films built around His Holiness released in 1997. Respectful, reverential to the point of deifying the Dalai Lama, Kundun is a beautiful but sadly hollow portrait of this historic figure.

Kundun shows the life of Tenzin Gyatso, a precocious, slightly obnoxious Tibetan boy. He is coddled a bit and somewhat entitled, but no one can explain why. That is, until 1937, when little Tenzin correctly identifies various objects belonging to the 13th Dalai Lama, declaring each "MINE!" in his child's voice.

Spirited off to Lhasa, he grows in wisdom and deep Buddhist faith while seeing the frailties of mortal man. His parents become comfortably wealthy, the man who found him grows greedy and eventually dies in the Potala Palace prison, leading the innocent Dalai Lama to ask, "Potala has a prison?".

He also faces the growing threat from the Chinese, culminating in the Communist invasion of Tibet in their effort to force Tibet to join China (or rejoin China, as the Chinese stubbornly insist Tibet has always been Chinese). The Dalai Lama is urged to flee, and he comes close, but ultimately is temporarily talked back into returning to Lhasa and even meeting Chairman Mao (Robert Lin). The Chairman, as pleasant as he appears to be, is not a man to be trifled with. Despite His Holiness seeing some common ground between socialism and Buddhism, Chairman Mao coolly informs the Dalai Lama, "Religion is poison". Seeing no alternative, the Dalai Lama goes into exile in India, where he still hopes to return to his native Tibet.

Kundun reminds me of two other films, both Best Picture winning biopics: The Last Emperor and Gandhi. Like the former, Kundun is the story of a child perceived as all-powerful and all-knowing, who can order adults around to do his bidding who ultimately is shown as powerless and forced into exile. Like the latter, Kundun is the story of an almost divine figure, who has apparently never sinned and who has a persona and personality that has him almost walk on water.

Herein lies the problem with Kundun: it is pretty but also pretty empty, a film of visual and audible splendor but hollow despite the admittedly beautiful trappings.

This was apparently a passion project for practically everyone involved. Screenwriter Melissa Mathison was active in the Free Tibet movement and devotee of His Holiness. So too is composer Philip Glass, who wrote the Oscar-nominated score. Director Martin Scorsese is one who searches out for spiritual themes in some of his films such as The Last Temptation of Christ and Silence, so Kundun's strong Buddhist spirituality would appeal to him.

However, again herein lies the problem. Kundun, both film and title character, are treated with such awe and reverence that the man behind the Ocean of Compassion is lost. Like with Gandhi, we never know the man behind the myth. The film spends far too much time and energy making the 14th Dalai Lama into this God-Man, one that almost makes Jesus Christ look like your wacky next-door neighbor. This Dalai Lama oozes divinity to an almost maddening manner. He is unsoiled by humanity. He is never cross. He is never happy. He neither cracks jokes or throws shade.

He is all virtues, no flaws.

It is interesting that in the Jesus miniseries starring Jeremy Sisto, Christ was able to tease his disciples and have a good time at the wedding at Cana. The figure many people hold to be God in human form had a sense of humor. The figure many people hold to be the reincarnation of a high Buddhist teacher, conversely, is gentility itself, forever horrified at the barbarity and cruelty of humans and forever calm, placid and serene.

Whether it is being informed of his father's passing or that the Chinese have invaded, nothing appears to affect or trouble His Holiness. Kundun takes the term "His Holiness" to almost hilarious levels, where one expects him to float off into India rather than bother crossing it on land.

Like with The Last Emperor, the title character is more an observer than the engine. The difference with the last pairing is that when it came to the actual Last Emperor, Pu Yi, his inability to shape history itself, let alone his own life, was the driving force of the film.

Kundun, conversely, puts the Dalai Lama at the center of events but they neither impact him nor does he impact them. They just happen around him, and despite his court waiting for him to make decisions, his primary decisions seem to be to let them do whatever they think is best.

In short, despite being the main/title character, there is no Kundun in Kundun.

The blame lies with Scorsese and Mathison. Scorsese has all his actors behave as though people have no emotions. He is too focused both on the visuals in Kundun and in showing reverence to His Holiness to take time on focusing on Tenzin Gyatso the man. Even the minor villain of Reting Rinpoche (Sonan Phuntsok), the Tibetan regent who found the reincarnated Dalai Lama but grew too greedy when it came to his reward, was almost more a shadow than a positive or negative entity.

Mathison for her part was simply too worshipful of the Dalai Lama. She clearly believed him to be quasi-divine, incapable of human frailties or frivolities. She looks upon His Holiness with reverence, but she also expects us to as well without giving us any reason to. Those of us who are not Buddhist will wonder what drives this man, why we should care about his particular plight, and Kundun does not give us reasons to.

It is hard to empathize or care about someone who is so far above us, so perfect, so pure, so holy.

The positives in Kundun are exterior. The film has a beautiful score, mixing West and East splendidly. It also has some beautiful visual moments courtesy of Roger Deakins' cinematography. It is not surprising that the cinematography and score were two of Kundun's four Oscar nominations, along with the film's costume and set designs. Each of them creates a beautiful, rich visual production that is a feast for the eyes and ears.

However, a rich visual and audible experience cannot make up for an empty production. Kundun is not a bad film, but an empty one. It is worth watching only as something to watch, to enjoy the vastness and visual splendor it presents. If you enjoy seeing and hearing beautiful images and music, you can enjoy Kundun. If you want to know the private man behind the reincarnation, look elsewhere, for Kundun is nowhere to be found in Kundun.

|

| Born 1935 |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.